A Response to OpenAI's Student Guide to Writing with ChatGPT

Guest post from Dave Nelson

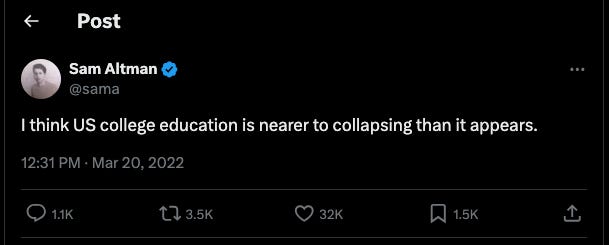

ChatGPT turned two years old and it’s not an anniversary many of us in education want to celebrate. ChatGPT has over 250 million weekly users, many of them students. OpenAI’s indifference to releasing an app that students used to offload learning is astonishing, but not unsurprising, considering Sam Altman’s thoughts about the state of higher education months before the public release of ChatGPT:

For the past two years, OpenAI’s grand public experiment included no guidance for educators. Early in November they finally released a student’s guide to writing with ChatGPT. The guest post below from Dave Nelson offers one educator's response.

Guest Post from David Nelson

On November 13, OpenAI published “A Student’s Guide to Writing with ChatGPT.” Arriving just shy of the two-year anniversary release of the public facing GPT3.5 chatbot and the eruption of “AI” into the public consciousness, this document suggests 12 strategies to help students use Chat in their writing and learning process, nestled between a brief wrapper about accountability and a caution against using it as a “shortcut to avoid doing the work, but as a tool to support [their] learning.”

Learning is gradual, cognitively demanding, and collaborative. It requires reflection, benefits greatly from interpersonal communication, and we know that memory gains weight from emotionally-valued experiences, which are almost entirely generated with and by other humans. This guide posits student learning work as something to be sped up, streamlined and dependent on a prediction machine. “Delegate citation grunt work to ChatGPT” is the first strategy presented. The tone is immediately condescending to educational practice. It suggests that learning tasks like reference citation work are beneath the learner, and unnecessarily laborious. The approach assumes superiority over Zotero and other reference management software that have been providing seamless citation formatting for decades at a fraction of computational energy. While the remaining suggestions are not so blatantly dismissive of educational writing tasks, they nonetheless reinforce GPT as a replacement for deeper thinking processes and the curation, expertise and decades of experience that educators embed in their teaching. The rest of the list asserts Chat’s supposed value in gathering information, structuring ideas into written form, and ideating.

Chat is generally promoted as a tool for experienced workers who want to remove repetitious or cognitive labor from regular tasks that require higher-order thinking skills. As a frequent user of large-language models since 2022, I have found many areas where Chat can supplement my daily communication writing with a reasonable degree of mimicry at fast speeds. LLMs can be useful generators of case studies or practice questions at scale, especially when given clear prompts and examples. Saving 20-30 minutes here or there can be a game changer when educators lack adequate time to tackle the myriad administrative responsibilities of their jobs. AI can accelerate a lot of individual expert cognitive work, especially when one’s ability to instantly evaluate the quality of the machine output has been honed by decades of practice. However, students rarely have such a practiced ability to respond critically to information.

Given several decades of engrained student practice with search engines, it is no wonder that AI companies want to lay claim to information acquisition. Google’s relatively recent “enshittification” after replacing engineering managers with financial marketers makes this an even more appealing business proposition. OpenAI encourages students to “quickly get up to speed on a topic” and “get a roadmap of relevant sources” to “point [them] in the right direction” in their research. The guide includes well-worded prompts like “What is Keynesian economics and how does it differ from classical economic theory”, along with an example output. For widely explored disciplinary concepts and definitions, this might be slightly quicker or easier than a visit to Wikipedia (again, with multitudes more compute power).

However, the example output is not verbatim or even paraphrased text from a user-curated encyclopedia, an academic textbook, or one of several hundred websites discussing economic theory. We do not know where it originated, since LLMs return a statistically likely output based on their training data and guardrails, and AI companies are famously opaque about the training process. But let’s accept that Chat will reliably summarize how replication forks work in E. coli bacteria or how an instant center of rotation is found. OpenAI wants students to accept its output as authoritative. Academic databases and publicly available search engines can also “provide foundational understanding of a subject” though they require learners to evaluate information by critically examining the source of an explanation. They also provide static, peer-reviewed articles with carefully sourced evidence and clear authorship. ChatGPT is a proficient mimic of some portions of writing, but like all LLMs, it is atrociously bad for source research. These machines are built to predict the next word, not to vet and verify wide swaths of scholarly work. Students would gain much more benefit by asking Chat for guidance and examples of queries that would make a database or Google Scholar queries more effective.

Assistance with logical and structural writing flow is one area where Chat might provide helpful guidance. Professional writing educators have been exploring student use of LLMs for this purpose over the last two years, and there are significant potential benefits, especially for individuals whose primary and secondary education have not repeatedly forged “the King’s English” into their word choice and writing patterns. The questions and prompts OpenAI offers mirror those from university writing centers. We still do not have conclusive data, but early inquiry into LLM-guided feedback for student writing seems promising. However, OpenAI’s hubris conceals a lack of curation. Student feedback requires context, calibration and professional facilitation. Disciplinary norms, theoretical approaches, intended audience and contextual knowledge of the individual learner are all subsumed with a chatbot that tries to be all things to all people all at once. Similarly, the guide exhorts students to “pressure-test your thesis by asking for counterarguments” aping the fundamental writing practice of anticipating and proactively responding to critical rebuttals. Here again the generalist bot works against intentional learning. Whose counterarguments are presented? Specific logical principles are likely not provided in response a generic prompt like “Which parts of my argument are solid, and where do I have logical inconsistencies?” Chat will not provide disciplinary decision-making structures, or choice points where the language organization of the model form the output.

Similarly, and most damning, OpenAI prioritizes throughout an individual interaction with a machine and excludes interpersonal learning. We know that learning is a social activity, that students gain deeper understanding in conversations with their peers, in collaborative spaces where their ideas are challenged, informed and tempered into stronger, more complex beliefs and values. OpenAI promotes Socratic dialogue where “ChatGPT can act as an intellectual sparring partner” and philosophical debates with historical theorists to develop and compare your ideas. This type of intellectual development is grounded in heterogeneity and interpersonal dynamics, both of which are antithetical to LLMs. And while Chat can provide a starting point for evaluating perspectives relative to established theories and ideas, it incentivizes shortcuts like “why read Kant when the machine can read it for me?” I’m intrigued by the possibilities of introductory learners asking Chat to “help me understand Kant’s impenetrable writing because it is really dense and give me examples of what Kant might say in response to my thoughts.” Yet, this learning would likely be done in humanities and social science courses, and those same activities could be accomplished with classmates and an instructor to much greater effect.

The superpower of large language models is their ability to infer quickly and to return a statistically likely mimicry of human responses to inquiries. Their great limitation is their homogenizing function and lack of dynamic interpersonal dialogue. This guide obviates human discussion and slow, considered ideation through writing. Other people are totally and intentionally removed from each step, driving students towards insular knowledge and beliefs formed with no purpose other than task completion, endorsed by a prediction machine. It is hard to imagine how this guide will further learners’ contributions to the written discourse of our complex and evolving society.

Note: No LLM chatbot was used in the writing of this article.

About David Nelson

With over fifteen years in teaching and learning development, David’s current role as Associate Director at Purdue’s Center for Instructional Excellence involves coordinating course design and development initiatives, including leading roles in many aspects of Purdue’s IMPACT course transformation program. He collaborates with academic and administrative units to foster innovative teaching, support the scholarship of teaching and learning, develop and promote individual faculty and instructor achievements in the classroom, and advise on general pedagogical planning at the course, department, college and university levels.

David is currently leading Innovative Learning's efforts to support AI and LLMs in CIE and Teaching & Learning at Purdue.

Thanks so much for this take on the guide! I am glad to see it, but it really feels too little, too late. Maybe intentionally so, from the vibe of that tweet from Sam A....

This is a reasonable critique. The truth is I don't think OpenAI has any real interest in helping teachers navigate the landscape they have created. What's curious about the suggestions / prompts they've created is they assume that students will use them in the way intended. My experience with student use of AI (albeit at the HS level) is that they have no idea how to write a prompt and the students that do understand how it works to get the best results are not the ones who we are really that worried about. Students who could really use the assistance to help with their writing / work habits are the ones who are least helped by AI because they are the ones who are most likely to use it poorly and for all the wrong reasons. At the moment, I think LLM's are just widening the achievement gap - strong students will perform better with targeted AI assistance and weaker students will bypass the learning process entirely and not get the skills. The bottom line is that, even with AI (perhaps especially with AI) teacher oversight and instruction is critical. I have used AI in an Independent Research class that I teach with some decent results but it's all while working directly with the kids, having them use GPT's I've specifically created for certain tasks, and as mentioned in this piece, helping it rewrite or draft prompts to use for other databases. There are useful ways to use AI with students but it is critical to preserve the human relationship. Honestly, I feel sorry for all sides of the equation - teachers who are thrown into the deep end when they have more than enough to do and students as well who are given this incredible temptation that they don't know how to use. This issue will not be going away anytime soon.