AI Is Unavoidable, Not Inevitable

I had the privilege of moderating a discussion between Josh Eyler and Robert Cummings about the future of AI in education at the University of Mississippi’s recent AI Winter Institute for Teachers. I work alongside both in faculty development here at the University of Mississippi. Josh’s position on AI sparked a great deal of debate on social media:

I’m not a fan of many of the issues associated with generative AI that Josh discussed at the institute or on social media; however, I’m seeing a greater siloing among folks who situate themselves in camps adopting or refusing AI. I’m glad Josh shared his ideas at this crucial time when we need to come together and have a much broader discussion about this technology as an emerging challenge.

Their discussion helped catalyze this post, but it’s not in direct response to Josh or anyone in particular. Josh’s critique of generative AI is one that many have stated. Some of this addresses points Josh brought up, but I’ve been thinking about them for quite a while now outside of their discussion.

To make my position clear about the current AI in education discourse I want to highlight several things under an umbrella of “it’s very complicated.”

The AI is Inevitable Hype:

I think generative AI is unavoidable, not inevitable. The former speaks to the reality of our moment, while the latter addresses the hype used to market the promise of the technology—a sales pitch and little else. Faculty and students have to contend with generative technology in our world as it is now, not as it is promised to be. That should be our focus.

We Need AI Across the Curriculum:

We cannot resist or adopt AI without knowing what it is. This technology is not static, nor should our understanding of its impact. Asking faculty from every department to teach students about this technology isn’t the same as calling to adopt AI tools for students to use. Our students are living in a world awash with generative tools and must be given opportunities to reflect on what their world looks like with this technology.

Generative AI Defies Analogies:

AI is not like a calculator. As Alison Gopnik so thoughtfully opined, generative AI is a cultural technology that is reshaping how we interact with information and each other. We haven’t had to deal with anything like this before. GenAI’s impact isn’t confined to academic assessments or student learning outcomes. The recent New York Times article profiling how quickly a young woman fell in love with ChatGPT’s voice bot should alarm all of us. It should also cause us to ask why.

What makes AI tools like ChatGPT Unavoidable in Education?

The majority of OpenAI’s 250 million weekly users are students. OpenAI and other generative companies have committed to release versions of their tools for free with few safeguards, in a massive public experiment that defies belief. There is no touchstone moment in educational history that compares to our current AI moment. If you think generative AI is like MOOCs, then I invite you to have a three-minute discussion about that very topic with a multimodal AI tool called EVI—Hume.AI’s Empathetic Voice Interface. You don’t even need an account, simply click the link and pick the synthetic persona of your choice. Get emotional with it and see how quickly it responds to match your mood. Do you still believe this technology won’t profoundly change education, labor, or even society itself?

Many of us have wanted to take a path of actively resisting generative AI’s influence on our teaching and our students. The reasons for doing so are legion—environmental, energy, economic, privacy, and loss of skills, but the one that continually pops up is not wanting to participate in something many of us fundamentally find unethical and repulsive. These arguments are valid and make us feel like we have agency—that we can take an active stance on the changing landscape of our world. Such arguments also harken back to the liberal tradition of resisting oppression, protesting what we believe to be unjust, and taking radical action as a response.

But I do not believe we can resist something we don’t fully understand. Reading articles about generative AI or trying ChatGPT a few times isn’t enough to gauge GenAI’s impact on our existing skills. Nor is it enough to rethink student assessments or revise curriculum to try and keep pace with an ever-changing suite of features.

To meaningfully practice resistance of AI or any technology requires engagement. As I’ve written previously, engaging AI doesn’t mean adopting it. Refusing a technology is a radical action and we should consider what that path genuinely looks like when the technology you despise is already intertwined with the technology you use each day in our very digital, very online world.

Unraveling Our Deeply Complicated Relationship with Technology

I write this post on Substack, owned by a large corporation that allows me to reach a wider audience than a traditional email or snail mail newsletter. Speaking of email, my home accounts are powered by Google while my work accounts are Microsoft—two of the largest corporations on this planet. The devices I type on are all made by Apple, also one of the biggest corporations on the planet. You might use a PC with a Windows operating system. Both Macs and Windows constantly monitor our usage to send back data to improve their products and pad their coffers. Very few of us have taken the time to explore open-source alternatives and install a third-party operating system like Linux.

I browse social media on another Apple device, my iPhone, liking and responding to posts on social media platforms that in turn monetize that data through advertising. Like many of you, I opened an account with Bluesky once Elon Musk took over Twitter and keep a presence across socials, but I’d be delusional to think each company isn’t going to sell my data or eventually fill my feed with bots trying to sell me something. My LinkedIn account not only advertises material to me but also scraps my posts to sell as AI training data.

I’ll pause writing this post, knowing that it is saved to the cloud before logging into my university’s LMS to update my course for the spring, which is hosted on yet another cloud. After that, I’ll work on a presentation and load it to Box—you guessed it, another cloud. All of these virtual spaces are made possible by data centers. Many of us aren’t even allowed to keep university data on hard drives anymore, which have shrunken because everything is now pushed to virtual storage. All of that has a cost, one we’ve agreed to pay by the very act of using it.

Every one of us is already so entwined with dozens of mega-corporations that we support daily through use with all the things that we find necessary to function in our very busy, very online lives, that resisting even one of those is a daunting task. The amount of energy, time, focus, and potential loss of access means we’re all unlikely to resist or look for legitimate alternatives to any of the tools or services I’ve mentioned above.

We Need Practical Solutions, Not Moral Outrage

This deep entanglement with technology raises a crucial question: How do we move from recognizing our technological dependence to making meaningful choices about new technologies like AI? The answer isn't found in moral outrage alone.

Our inability to disconnect from technology and make critical, informed decisions is the problem I’d like us to explore, not simply generative AI. We are all complicit actors in these dark techno-deterministic tales, many of which are spun by the very forces that hype AI. After all, what better way to sell a product than to convince people it can lead to both your salvation and your utter destruction? The utopia/ dystopia narratives are just two sides of a single fabulist coin we all carry around with us in our pockets about AI.

We’re not seeing things very clearly. Take Marcus Luther’s post on X about the current obsession K-12 schools have over banning cell phones v. other types of screens makes me think we’re likewise missing the greater point about AI in education, namely how intertwined and problematic our teaching is with the technology we have now. Did we refuse the modern university when it arrived with its current technologies that we suspect may hinder student learning in our classes?

We Need Better Frameworks than Resistance v. Adoption about AI

We should all advise people to be cautious and skeptical about generative technology because we know very little about how it will impact our lives, not base our objections on value-based judgments about the ethics of using one form of technology v. another in a vast sea of already deeply unethical innovations we all consume daily.

In many ways, we’ve become a society immune to the absurdity of its interests. Social media and call-out culture haven’t helped. A person will decry another’s AI usage as environmentally damaging on social media while waiting for their flight to Greenland to catch one last glimpse of the glaciers before they melt. We read study after study about how much water it takes to cool data centers, yet find no issue ordering avocado toast or asking for almond milk with our Starbucks—knowing that both consume countless gallons of water to produce.

Right now, generative features appear like countless potholes in the digital roads well-traveled by us all. We can only swerve so often before hitting one. The road isn’t going to change.

AI resistance and AI adoption are more performative at this moment than actionable. On one hand, you can choose to not use tools like ChatGPT but to refuse generative technology and its influence means making countless decisions to opt-out, turn off, and shut down so many features in the apps we use daily. In terms of your students using AI, you have no such option outside of persuading them to opt out. That said, adopting AI isn’t really possible either because most of us don’t have the capacity to truly adopt something that changes so dramatically so often. You not only have to seek out the AI tools, and pay for the most advanced options on the market, but you often have to figure out the use case for the thing you’ve committed to use—all while keeping up with the endless updates and new features.

AI’s Impact Isn’t Simple to Gauge

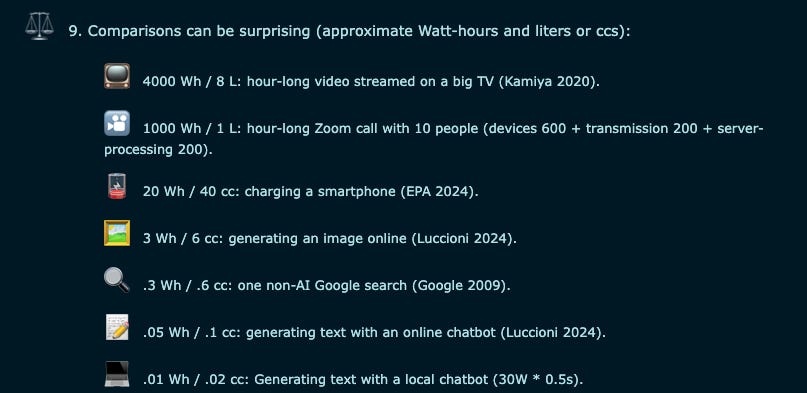

AI’s environmental impact is one of the most often cited objections to using generative tools. But like nearly everything to do with our discourse around this technology, AI’s energy usage is complex and difficult to pin down. Jon Ippolito’s recent essay AI's impact on energy and water usage does an excellent job of navigating the the discourse with a "just the facts” approach. What he finds is a very different result than what we hear about in the press. Namely generating text doesn’t use much energy compared to streaming an episode of Netflix.

Jon cites Hanna Ritchie’s recent essay What’s the impact of artificial intelligence on energy demand? Ritchie uses data from the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook Report. The big takeaway from Ritchie’s article and her analysis—we aren’t having good conversations about AI and energy usage. Data centers as a whole only use up around 1% to 2% of total energy demand. Most of that isn’t from AI. It comes from a mix of social media, data processing, and cryptocurrency. AI won’t be a major contributor for quite some time and when it is, AI will fall into that 1% to 2% category.

The thing is, Jon welcomes people who contradict his findings, which is exactly what we should all be doing; otherwise, what’s the point? We all extoll sources that speak to our values and put up blinders that might cause us to question those beliefs and that’s caused us to fracture into tribal bands, arguing over our values instead of analyzing evidence and being prepared to change our stance.

The Myths of Sustainable or Ethical Technology

What are we resisting when we refuse generative tools and why is AI so much different than the other modern technology that we adopt and cannot seem to live without?

I think we’ve failed to articulate that effectively for ourselves and also our students. We need to break down and analyze our own relationship with technology, and doing that involves acknowledging our own messy and often morally dubious relationship with tech.

The screen you are reading this on, like the smartphone in your pocket, wasn’t ethically sourced or sustainably made. The labor used to mine those resources and assemble the final product was invisible and exploitative—like so much of the economic forces that fuel our reality. That companies like OpenAI relied on similar power dynamics to source cheap labor from the developing world to train generative tools like ChatGPT isn’t a surprise, but taking an ethical stance about it creates a fantastical version of good v. bad technologies that borders on the absurd.

We have to put into context the narratives of soulless mega corporations destroying the hapless and unaware users and instead do the much harder work of analyzing and studying our own technological adoption as a cultural force worthy of inquiry and debate. Our students deserve spaces where such inquiry is welcome and not boiler plated away behind pro-AI adoption initiatives or anti-AI policies within our institutions or our courses.

What Educators Need Now

Engaging AI in education requires far more resources and time than anyone wants to admit. It also calls for a level of nuance we’re not going to find on our social media feeds. I don’t know enough about generative tools and you likely don’t either to make the important decisions necessary to chart the best path forward for myself or my students with the AI we have today, let alone the AI that is on the near horizon. We need support from local and federal agencies, policy initiatives that promote careful innovation, not reckless deployments, commitments to treat AI literacy across the curriculum as a continuum, time to explore the tools and use cases, communities that seek consensus over siloed positions of for or against. The work ahead is going to be hard. All the more so because we’re not going to catch a break from AI developers shipping new features and updates.

Most importantly, we all deserve some grace here. Dealing with generative AI in education isn’t something any of us asked for. It isn’t normal. It isn’t fixable by purchasing a tool or telling faculty to simply ‘prefer not to’ use AI. It is and will remain unavoidable for virtually every discipline taught at our institutions.

If one good thing happens because of generative AI let it be that it helps us clearly see how truly complicated our existing relationships with machines are now. As painful as this moment is, it might be what we need to help prepare us for a future where machines that mimic reasoning and human emotion refuse to be ignored.

Really helpful perspective across many fronts. In terms of framing an approach, I see things mostly similarly. In More Than Words, the concluding chapters are titled Resist, Renew, and Explore, where I first articulate what should be resisted (e.g., anthropomorphizing LLMs), and then move to what we should renew (human connections, writing as an act of valuing a "unique intelligence") and then moving on to what we must explore (the ways technology can enhance human flourishing).

The challenge, as you articulate here, is that we're trying to do these things simultaneously and the ubiquity of the applications and speed of change (the unavoidable stuff) leaves it hard to pause and orient in ways that allow us to explore productively. My call in the book is to try to make space for the foundational work first, but it's clear this is not an easy thing.

Marc,

Enjoyed this post a lot as I think you weave together so many of the issues about how the infrastructure and sharing of data across all platforms are deeply embedded in everything we do - AI is simply another layer on top of that. I was also intrigued by the environmental analysis you include here - have not seen those numbers anywhere else and most coverage of AI and its effect on the environment seldom put it into the context you do here. One other point and I would be curious of other educator's take on this - my school is involved in something called the RAIL (Responsible AI in Learning) program (https://www.msaevolutionlab.com/rail) and I'm early in the modules, but a very clear point that is made repeatedly is NOT to think about AI as being "integrated" into existing practices but to do a total "reimagining of teaching and learning" - this strikes me as Pollyanish and idealistic and, even if true, seems unlikely to me to happen anytime soon. Most of the "use cases" you see out there are about using AI to do what we have always done (integration), just (theoretically) more efficiently and more effectively. What RAIL is suggesting is this will fail in the long term. To do what they are asking requires a wholesale re-evaluation of educational practices which most schools have not been capable of even before AI came on the scene. I don't know if they are right, but I do understand their point. Just another piece of the puzzle that raises the bar regarding all these issues being dealt with at once.