Last night, I wrapped up the sixth conversation with ChatGPT’s plus voice conversation assistant and I feel so weird having spent time conversing with a synthetic voice, driven by synthetic text. And yet it felt so much more vibrant than my experiences with Alexa or Siri. I used the new feature to mimic a brainstorming session using the Juniper persona and each question or exchange greeted me with an incredibly stylized response. It recognized my speech, and my tone, even detected pauses, and synthesized it all in a coherent and bizarrely human-like response. I even played around with some prompt engineering and asked it to hedge, use a more natural voice, embrace ambiguity, and talk to me like I was a teenager. The AI’s response was nimble and adapted well to those commands. Maybe too well.

It’s eerie to think about how quickly we’ve arrived at a point where a transformer specially trained in language synthesis can now engage with the sensory experience of sound, speech, and vision. Those who cautioned against anthropomorphizing the technology are going to have their hands full as Big Tech continues to introduce these new features. It won’t be long before we start wondering if the video recording we’re listening to, the book on tape, or even the virtual conversation we’re having with a customer service agent is with a synthetic voice.

We fell into a bit of an analogy hole with generative AI and this hasn’t helped people understand the full capability or limitations of the technology that’s being deployed and scaled at unbelievable rates. The chatbot interface is just one instance of the technology. These new capabilities defy easy categorization because they are not only so new but also so akin to the human processes it was designed to mimic.

So many have said “It’s like a calculator” that we risk turning the phrase into a cliche. Sure, I suppose you could talk about text synthesis generated by AI in a simple input/ output analogy based on preprogrammed rules that we’d find familiar examples with a calculator. But that misses something profound—the input isn’t just text. Anyone can string together words and produce an output with generative AI, just like most able-bodied people can learn how to ride a bike from point A to B, but to create a meaningful output using the technology requires a sense of wordplay, foundational knowledge of rhetorical purpose, and above all, an understanding how language functions. It’s the difference between handing someone a bike and expecting them to pedal a few yards successfully, vs. telling them to enter the Tour De France and expecting them to place in the top ten. Neat analogy? Sure, but in seeking familiar footing I’ve massively undersold what’s taking place.

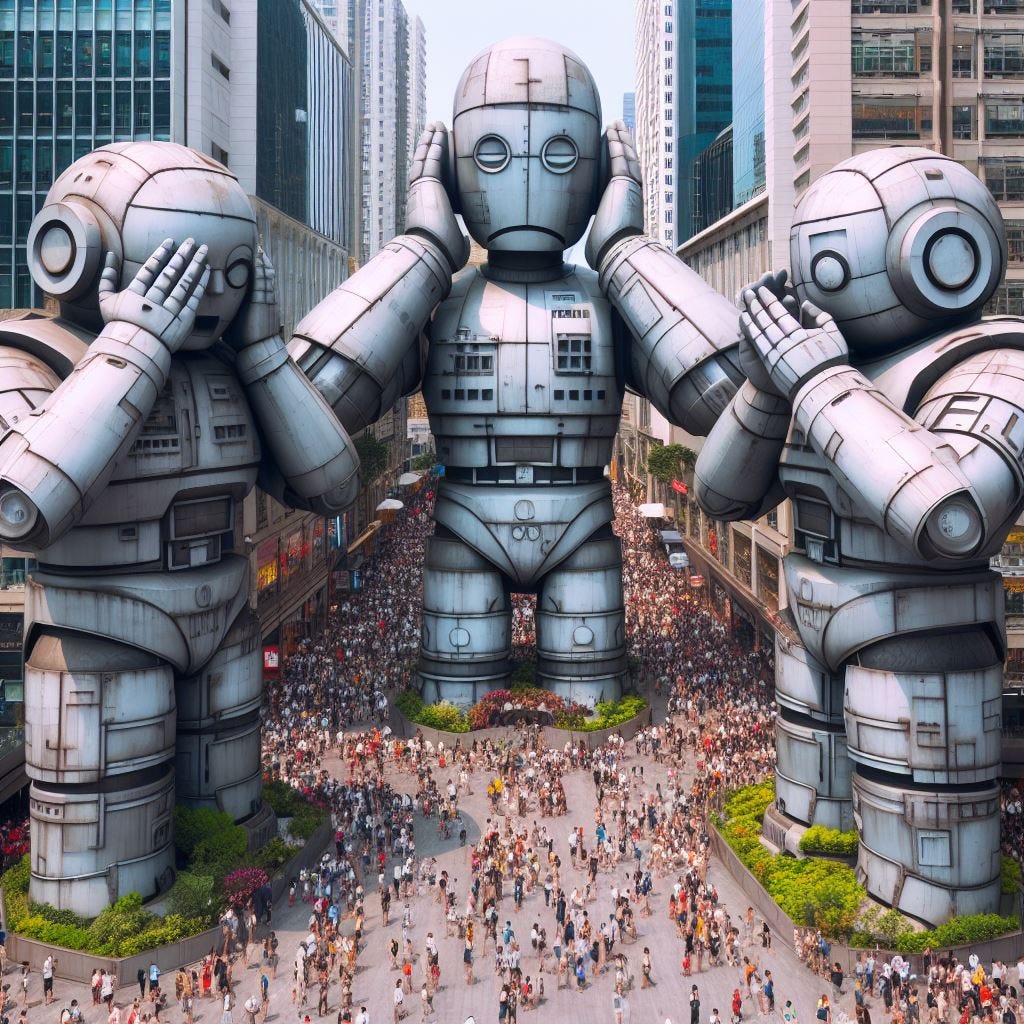

With the launch of vision and now speech for ChatGPT Plus, we now have to move beyond the simple comparison and start to see how multimodality defamiliarizes those old analogies. We lack frameworks to fully make sense of an AI that synthesizes key facets of human interaction. As engineers rush to connect more sensory experiences to LLMs, the well-worn standby of “it’s just a tool” doesn’t quite capture the monumental shift of what’s happened.

Too much has changed too quickly for us to consider the implications of speaking, listening, and vision-enabled LLM. We’ve been so focused on goal-posting what a language model can do, dunking on how canned and generic the responses are, delighting in hallucinations, that we missed the greatest and frankly terrifying implications—we’ve created a machine that can predict responses at near human level, and use techniques that mimic seeing, reading, speaking, listening, and deployed it in the pockets of millions for $20 per month.

Pigeonholing these advances into familiar categories undershoots their significance. With vision and speech integrated into widely available services like ChatGPT Plus, we’ve crossed into new territory. The central challenge is no longer determining what these systems can and can’t do. It’s developing new conceptual models to understand what’s happening, where it might go, and how to responsibly steer technological capacities that increasingly mimic human faculties.

This requires moving beyond analogies designed to create comforting familiarity. We need to engage directly with the unique capacities emergent generative AI represents, with clear eyes on both possibilities and pitfalls.

Now that I’ve heard it and spoken to it, I can see how an automated system that’s always on, mimicking a mentor, a teacher, a tutor, or a companion can be a catalyst that drives profound change. It will also certainly further fray the relationship many have with reality. Students will learn from it, the needy will find a friendly voice, the lonely will fall in love with it, the desperate will seek satisfaction in abusing it, but above all, people will use it because it is the closest we’ve come to the promise of a science fiction fantasy.

Great piece, Marc. Strange days, indeed