It's Time to Train

Faculty need resources and time to process generative AI's impact on education

-Robot weightlifting a college professor, Lexica

The spring semester is ending and by mid-May I’m scheduled to give my 30th presentation, talk, panel, podcast, workshop, etc. on generative AI since August of 2022. It’s been exhausting, but I think the real work has just begun.

In early June, I’ll direct an AI Summer Institute in collaboration with the Department of Writing and Rhetoric and the Institute for Data Science at the University of Mississippi. The institute will offer a two-day-long immersive boot camp into AI literacy for UM faculty. It will be designed as an introductory workshop, geared toward teachers of writing-intensive courses, to help faculty prepare for the fall. I anticipate many institutions will need to replicate something like this and do even more beyond an introduction to what these generative AI systems can and cannot do.

The urgency of offering faculty some type of structured professional development this summer couldn’t be timelier, or fraught with challenges. Microsoft will soon release Copilot, their version of the Office Suite with fully integrated GPT capabilities in everything from Word to PowerPoint. The notion of banning generative AI, like ChatGPT, was never really feasible, and now that it’s integrated within the #1 selling productivity software on the planet, it isn’t even remotely possible. I think most of us will agree that the need is there to educate and train faculty about this emerging technology, but how do we do this while it deploys in real-time around us?

Do we advocate for methodologies or specific approaches to teaching alongside AI?

Do we encourage faculty to adopt techniques to alter assignments and assessments to make it harder for students to use AI?

Do we pursue increasingly intrusive surveillance methods to try and ensure academic integrity?

Do we train faculty to design assignments and assessments using generative AI?

How do we navigate the increased labor generative AI poses to NTT faculty and K-12 teaching?

How do we balance learning while promoting skills future employers will want from an AI-literate workforce?

These are a few of the questions I’m left pondering. We’re going to need to see a lot of different styles and approaches, a lot of trial, error, and utter fall-on-your-face failure before we arrive at anything resembling a coherent approach.

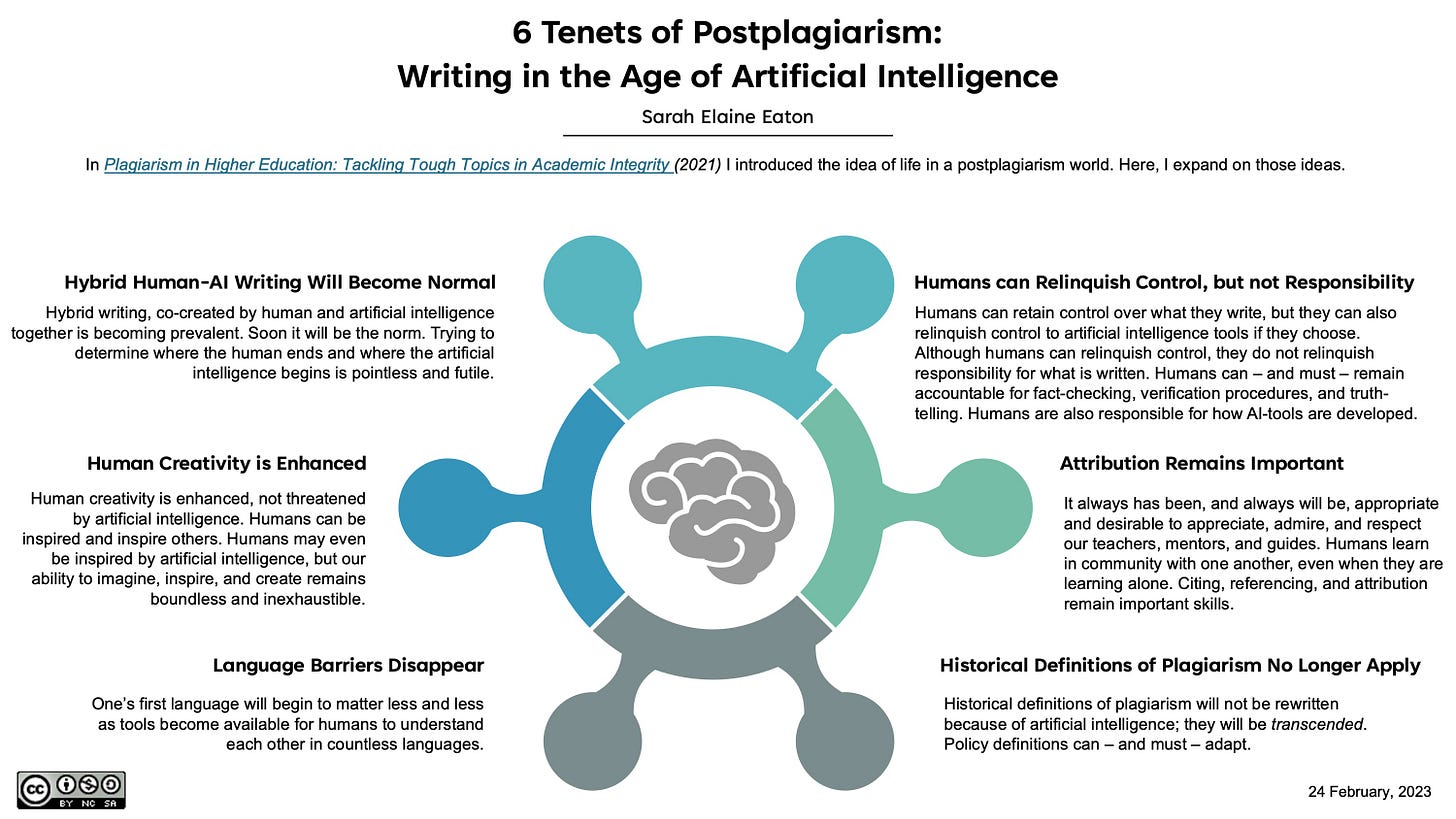

Our Post-Plagiarism Era Arrives

One thing that is clear to me is having some neat little boilerplate pasted on a syllabus about AI generation isn’t going to cut it. Faculty and students need more than policies to navigate what may be a fundamental shift in literacy and how knowledge is created and consumed. I really like Sarah Eaton’s thoughts on generative AI’s impact on academic integrity. Her argument is both articulate and convincing that we have arrived in a new era of post-plagiarism in academic writing, one where we will have to accept some level of hybrid human/AI-generated authorship from our students and our colleagues. What new policies will arise from this is beyond my guess at this point, but I am hopeful to see a dialogue begin to form within academia and outside of it about what this shift means for writing.

The one thing I don’t look forward to witnessing is the tribalism and siloism of different camps on generative AI in education. I’m seeing this currently in the broader field of AI and it isn’t the type of water I want to tread. This rapid and often reckless deployment of generative AI is an emerging challenge that calls for greater dialogue and engaged discourse rather than diversion and discontent, and I don’t see bickering as the way forward.

We Should All Become Digital Gardeners

One of the reasons I started this substack was as a place to order my thoughts, organize the information I’d been collecting about generative AI, and try and make sense of it all, before engaging in a broader conversation. I didn’t understand at the time that making this process public online was what some call digital gardening. I may not have developed aa green a digital thumb as others, but I’ve really come to value this concept as of late, especially when I read Maha Bali’s What I Mean When I Say Critical AI Literacy and Anna Mills’ thoughts on GPT-4s impact on education. To me, these are both apt examples of digital gardening. So is Ethan Mollick’s One Useful Thing and Brenna Gray’s TRU Digital Detox series.

There’s no mainstream approach to engaging generative AI in education, no list of accepted best practices, no do this, don’t do that. Generative AI in education is an emerging field developing before our very eyes and requires each of us to become something of a digital gardener, collecting information from various sources, cultivating certain ideas, and letting them flourish, while weeding out others or letting them wither when they are no longer relevant or helpful. It requires us to share our thoughts and plant our own ideas, often over extended periods, in the public discourse to arrive at an ethos on generative AI in education.

Now that Twitter is throttling third-party API access, I’m not hopeful that we’re going to be able to use one of the most productive spaces to share those ideas. The dream of the fediverse offered in social media outlets like Mastodon seems very much so out of reach in establishing an alternative to this messy, chaotic, and oftentimes raucous discourse we see on Twitter. It simply serves as yet another reminder of how little the public has any sort of say in how massive corporate interests shape our digital discourse. I hate to leave things on this note and really hope we aren’t seeing the end because I have so valued many of these interactions.

It's easy to become overwhelmed by all of this. Thank you so much for your insightful writing, Marc! So helpful!