What does it mean when we stop reading texts and instead offload that skill to AI? We desperately need another ChatGPT moment outside of text generation to wake people up and let them know how quickly generative technology will impact skills beyond writing. For $5 a month, anyone is now able to summarize and query a PDF using Adobe's AI Assistant. You can already do this with a number of foundation models, along with a slew of purpose-built AI-reading assistants. Who is talking about this? We've been so laser-focused in education on ChatGPT's impact on writing that we've missed generative AI's impact on a multitude of core skills, like reading.

The implications of having an AI-reading assistant that can summarize anything into your language, at your reading level, can have immense benefits for neurodiverse learners and second-language learners. AI reading assistants could play an important role in equity and access to information. However, the uncritical adoption of AI reading tools poses an incredible risk to student’s close reading skills.

Last year, I piloted two purpose-built AI reading assistants within my first-year writing courses to see what affordances they might offer students in a controlled reading of a text. I recently published a chapter in Teaching and Generative AI: Pedagogical Possibilities and Productive Tensions about this experience using ExplainPaper and SciSpace to augment reading. Students overwhelming loved the tools, but the pilot caused me deep concern. Like so many different tools that use generative AI, I found the reading assistances were focused on speed and task completion over nurturing developing skills or honing existing ones.

This isn’t to say there aren’t profoundly helpful use cases for the tools beyond students who struggle with reading comprehension and language acquisition. Who wouldn’t want the ability to summarize massive volumes of information with accurate and automatic summaries? A lawyer could go through case law at unbelievable speed. So, too, could a researcher on any subject. But is the purpose of reading in these instances simply to arrive at information that fills a brief or a pad a report? What about an overworked adjunct who has to read and comment on 100+ rough drafts? I think you can see how quickly a tool that promises efficiency can challenge the boundaries of an existing practice.

How AI Reading Is Marketed To Students

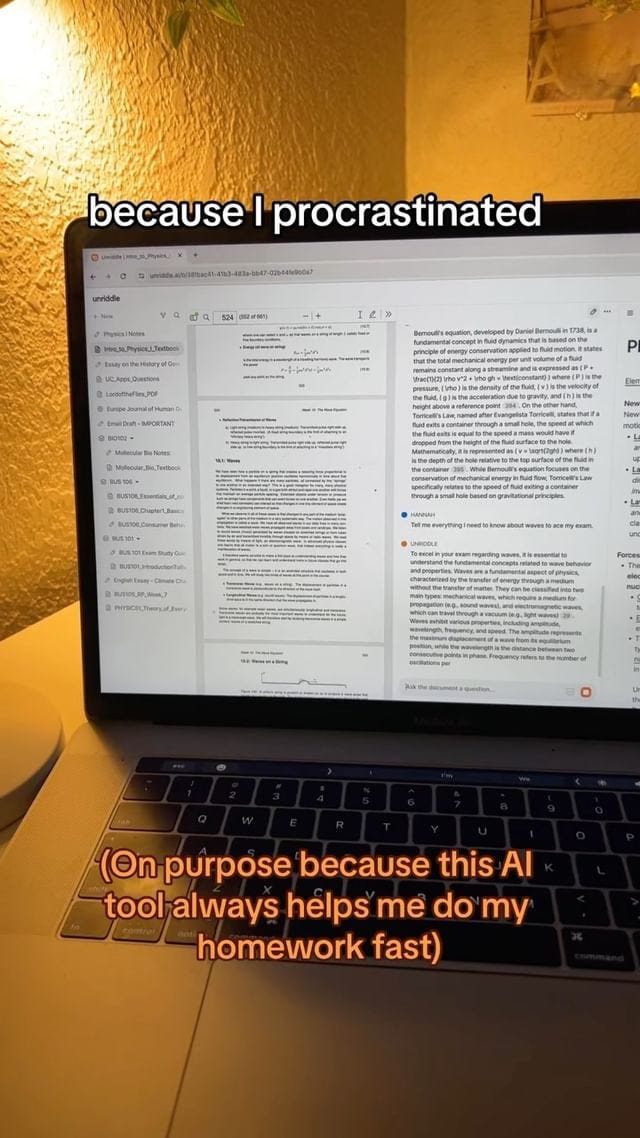

A few months ago I wrote about The AI Influencers Selling Students Learning Shortcuts and I mentioned how apps like Unriddle AI promise to read for a user and are inundating social media with marketing directed toward students. Some of these posts have a million plus views and all use influencers about the age of students to market AI as a time saver. What they don’t mention is how often an app like Unriddle misses key facts from a document. When the selling point is speed over process, nuance and accuracy are often left behind.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Why Reading Matters

When we teach reading as a skill, we’re asking students to practice more than analytical thinking through close examination of a text—we’re inviting them into a conversation with the reader about their ideas. We want maturing readers to engage with the text, not a summary of it, because we know that doing so means those ideas can help shape and mold a student’s thinking, challenging their assumptions, and making them argue within themselves over deeply held beliefs they may have about our world. A bespoke generative summary just doesn’t do that. If students adopt it as a replacement for close reading, it may rob them of the opportunity to fully engage with an author’s ideas.

If we allow an over dependence on AI reading assistants to undermine students' ability and willingness to closely read and engage with texts, the ramifications could ripple across society for generations downstream from our classrooms. Without skilled critical readers, we risk producing minds that are primed to accept neatly summarized information at face value rather than question it, analyze it from multiple angles, and draw their own nuanced conclusions. This hollowing out of one of the cornerstones of higher-order reasoning could severely inhibit innovation, civic discourse, and our collective capacity to thoughtfully navigate complex issues.

Unchecked, the lure of frictionless reading could produce a profoundly atrophied culture of surface-level ideas rather than exploring them in depth. In such a world, I shudder to think how blind obedience to authoritative-seeming AI outputs could allow misinformation and weaponized narratives to proliferate unabated.

I’m a fiction writer by training and spend a great deal of time honing my craft beyond the plot of a short story. I think about how the language sounds, the order of information, and the rhythm, and timing of sentences. If I load up a short story by James Joyce or Flannery O’Connor to an AI reading assistant it will generate a plausibly accurate summary of the sequence of events within the narrative, but asking for an analysis of the craft of the story is a complete failure. More so, asking an AI to change the reading level of a story written for an adult audience for a middle-school grade level removes nuance, style, and distorts artistic intent.

Uncritically adopting an AI to read for you is far more dangerous a threat to knowledge acquisition and learning than using AI to write for you. We need to navigate a path that advocates for ways for students to use this technology ethically to support their learning and not in a manner that will deskill them because it offers the siren song of timesaving through a frictionless experience.

We Should Embrace Learning Through Friction

I’m convinced we need to move away from policies allowing for or against AI and instead examine ways to negate the most disruptive parts of uncritical adoption. We should introduce friction into the reading process of a digital text, not to make it more challenging, but to ensure students slow down and process a text. Educators can do this for digital readings through social annotation tools like Hypothesis and Perusall.

Creating active reading assignments where students are required to annotate a text and discuss it with fellow students slows down the process and adds friction to the experience. It also makes the reading a social activity as opposed to an individual one and invites inquiry and debate within the reading process. This added friction isn’t there to make the process of reading harder or easier—it exists to ensure students engage with a text and focus on the act of reading for self-discovery and insight over the speedy affordance of using an AI reading assistant to summarize a text for them.

The stakes are ridiculously high when it comes to reading and AI and I wish more people knew about it or had the bandwidth to think about what is gained or lost by generating a summary of a text instead of reading it. Below is how I concluded my article on reading assistants. I hope you will read it and not use a machine to generate a summary.

In conversation with students after the assignment, I asked them some pointed questions about what it might mean for their future learning or careers if they employed such a tool each day. Many were delighted at the prospect of not having to read for school or work, but when I asked them what their response would be if I used a reading assistant to offload the process of reading an assignment they submitted, or if their employer did the same, many students began to put the short term affordances of offloading reading into the greater context of why reading is a foundational skill for our world. Some pushed back at this notion, saying AI is no different than any other tool and why shouldn’t use it all the time if it is available. I wish I could tell you that I picked up my favorite book and read passionately from a passage as a response, but in truth, I understand where students are coming from. They weren’t reading for enjoyment or pleasure—reading in this context for them was a utilitarian act, a labor, a means to complete an assignment to reach their desired ends—a successful grade. I find that dichotomy present in nearly every conversation about using generative AI in education—learning has been reduced to a problem and here is a technological solution to help solve it. Now that generative AI technologies are commonplace, educators are going to need to fundamentally examine and articulate the importance of human skills and the value they have. Otherwise, many of our students will simply adopt the tools uncritically as solutions and stand-ins for many of the core skills we associate with learning.

Honestly, I think this a far more important conversation to have than about writing, and not just because there are risks to AI proliferation but it's the one area where I see room for AI to act as a useful prosthesis of sorts. We're actually deeply familiar with guides of various kinds intended to facilitate reading or to accelerate transmission of information. Some of them are inside of texts--table of contents, index, glossary, chapters, subheadings, abstracts, annotations, footnotes, etc. Some of them are texts that help with a text--concordances, summaries, commentaries, book reviews. We're familiar with the advantages and disadvantages of using something like "Cliff's Notes" or "For Dummies" guides prior to trying to read a text, but we also acknowledge the necessity of needing help simply by the fact that we teach classes *about* a particular text, that many things cannot be read in isolation or in solitude. For some texts, no one would argue that you have to make sense of it without assistance--Finnegan's Wake, for example. Many of us are operating with vast systems of paratextual knowledge--e.g., we know about the content of readings that we haven't done, and our knowledge is often basically correct. We know there's a value to reading a text deeply and well but we know it's not an infinite value--that there are trade-offs (of time, of efficiency, of necessity, and of affinity--no one wants to struggle profoundly with a reading that they have come to hate or feel alienated by).

What I find strange is precisely what you start with here in your title: literally no one is talking about this aspect of AI. But that is perhaps partly because we oddly treat reading as a lower-level pedagogical job, to be attended to in secondary education. There is very little conversation generally about how to read past high school, only a lot of moral panic about *whether* people are reading enough or reading the right things.

Good work!!! I have a draft on this subject in the works!!! Now I will pick up where you leave off.