NotebookLM and Google's Multimodal Vision for AI-Powered Learning Tools

Everyone started talking about Google’s NotebookLM because of their recent podcast update, but the real story is about how Google is using its AI experiments to push our understanding about how people will use generative AI as tools for thought. The podcast feature is a seemingly simple use case that Google Labs had been testing for some months behind the scenes in a project called Illuminate, with an intentionally limited library of open access and out-of-copyright material. But it made a major splash when they activated the feature in NotebookLM. Google’s AI experiments are vast and pose some of the more intriguing use cases, but like all generative AI tools, they are being deployed as public experiments, giving us little time to understand how they impact learning before they are accessible to students.

Responsive to Criticism

The team behind Google Labs responded to public criticism that there wasn’t a transcript to accompany the generated podcast in Illuminate and already implemented the feature, which is welcome news to see a developer respond to make a tool more ADA-compliant. Let’s hope NotebookLM does the same.

There may be some deeper hurdles ahead. Illuminate only lets users generate podcasts from open-access articles, but the Audio Overview feature in NotebookLM doesn’t have such restraints. Hearing an AI-generated podcast of a source is an impressive feat, but do we have consent from the copyright holder to create a generated podcast that does more than simply summarize the material? This goes into the question of using AI to transform text and begs greater legal and ethical questions that many educators simply don’t have the bandwidth to tackle.

The Limitations of RAG v. Long Context Windows

NotebookLM has been on the market for a while now. I first wrote about NotebookLM back in October 2023. At the time, it was an interesting experiment using AI to talk to your data, but the overall interface was clunky and used a poor-performing LLM. The results were lots of hallucinations and an extremely limited set of file types you could upload. Many of those issues have not been resolved during the most recent series of updates.

NotebookLM uses advanced retrieval augmented generation (RAG) to establish vector embeddings in the data you upload. That’s part of the reason why users can upload so many files to it—the AI creates summaries of each file. This might go well beyond their published 4,000,000 million word upload limit and give users up to 25,000,000 words per notebook. At least that’s what Steve Johnson claims on Twitter.

RAG isn’t the same as long context understanding used to ‘talk to your data,’ like Google demoed using Gemini 1.5 Ultra. But that’s not going to be an issue for most use cases that stay under 10,000 words per notebook. That seems to be the sweet spot for the immediate context window before RAG kicks in, and with it comes increased hallucinations.

A Variety of Use Cases

Create an Interactive Syllabus

You can upload your syllabus to a notebook and invite students to explore your course. Give students a series of questions they need to ask about your class and combine it with reflection to make your first-day class activity more lively. As a bonus, you can generate a podcast of your syllabus and have AI-generated voices talk about your course. You still need a transcript, though!

Presentation Deep Dive: Upload Your Slides

As a teacher, you can upload your Google Slides to a notebook and have students use AI to explore your presentation. You can generate a podcast of that presentation topic using the Audio Overview feature and upload it to YouTube so that it is properly transcribed.

Note Taking: Turn Your Chalkboard into a Digital Canvas

You can upload images to NotebookLM, but the process is . . . complicated. You need to save your image files as standalone PDFs with no added text in the file. That means the AI will read images or even handwritten notes, but will bypass them altogether if it detects any sort of typed text on the file.

One immediate use case is using NotebookLM in conjunction with analog learning. Have students brainstorm organically during class, writing their ideas on the board. At the end of class, take a picture of the activity and load it into NotebookLM. Share the notebook with students and invite them to explore what they learned in class using AI as part of a deep dive homework assignment.

Explore a Reading or Series of Readings

With a massive context window of 50 sources per notebook, users can start exploring some truly far-out use cases. Having students explore a variety of sources using AI to help them find connections at a speed and scale is something we’ve not prepared for. Be mindful that each use case like this brings with it potential perils. We want our students to develop synthesis skills on their own outside of AI. There are also consent and copyright aspects to consider.

Help Navigating Feedback

Students often receive conflicting feedback from classmates during peer review sessions. They can use generative AI within NotebookLM to help them navigate that. One example is having students upload their rough draft and all peer reviews to a notebook before prompting it to help them navigate all the different types of feedback. And, of course, they can generate a podcast overview of that feedback exploration.

Portfolio Building Blocks

In Writing courses, we often ask our first-year students to reflect during each class meeting about what they’ve learned, and then assemble that into a reflective portfolio at the end of the semester. With NotebookLM’s context window, students can upload all of their completed course work, including reflections done throughout the semester, and ask the AI to help them find connections showing what they learned throughout the semester.

Google’s Labyrinth of AI Experiments

You can find NotebookLM and the stand-alone podcast tool Illuminate in Google Labs. This testing ground has familiar apps, like Google’s AI overview feature, alongside some wilder use cases in coding, MusicFX, VideoFX, and ImageFX. Google is testing all of these models at different stages, with education tools like Illuminate and a generative research tool called Learn About nestled in between. Some of these are available, others are in private testing. You can spend hours exploring these features.

Here’s a brief run-down of the different AI experiments Google has going on right now. Mind you, this is all in addition to Google’s main Gemini app and their introduction of generative AI tools into Google’s Workspace:

Google’s AI Test Kitchen:

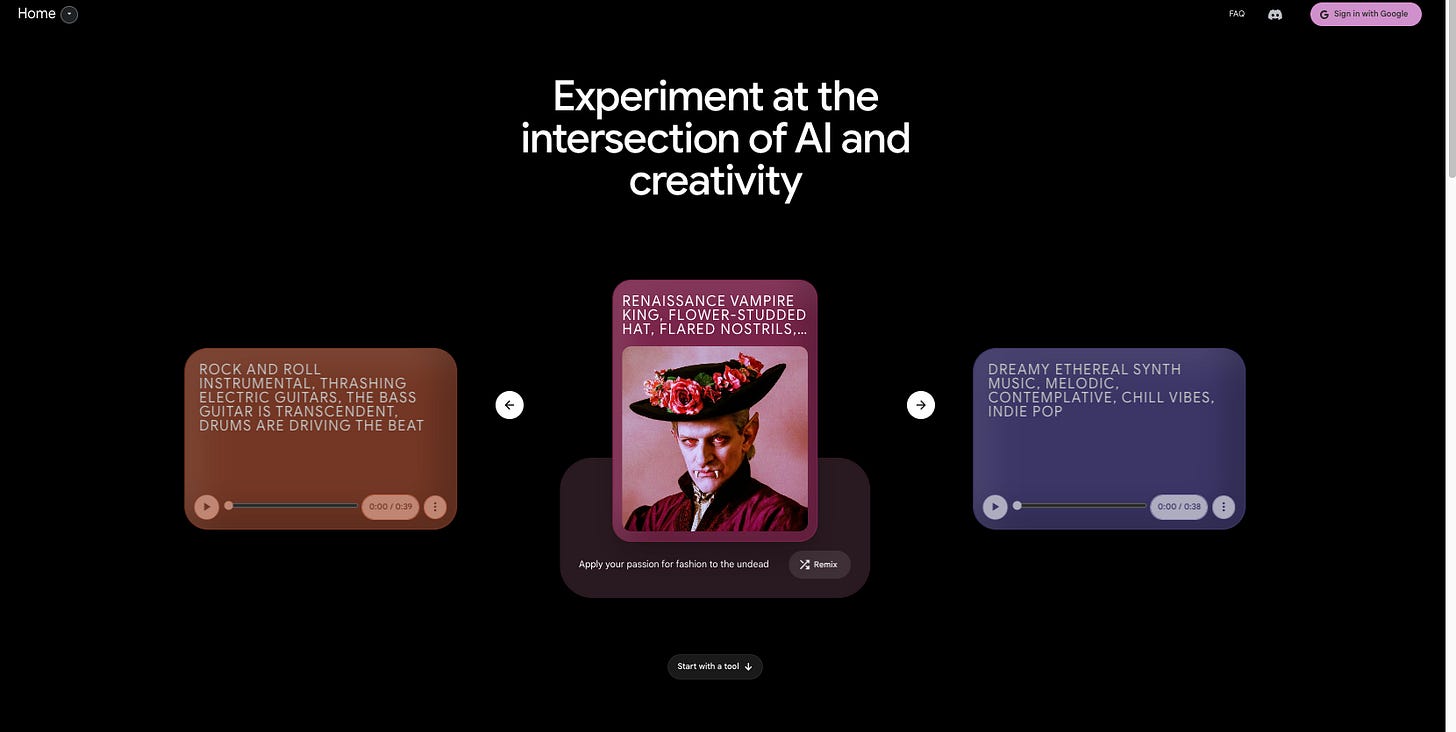

This site hosts all of Google’s FX suite of tools, which are all also hosted on Google Labs, so it isn’t really clear why it exists as a stand-alone site.

Google’s AI Studio

This site allows users to access Gemini 1.5 models, not to be confused with Google’s main Gemini chatbot interface. AI Studio lets users preview Google’s most advanced multimodal models and upload 2,000,000 tokens per chat! It’s geared more as a developer playground than the public facings Gemini chatbot.

Google’s Arts and Culture AI Experiments

Yet another stand-alone site is the ongoing Arts and Culture AI experiments that contain dozens of different educational games that use generative AI to help students explore classic works of art, artistic movements, and different cultures from around the world. There are some truly amazing use cases here that I covered back in January.

How these different sites that host so many AI experiments fit into an overall strategy to incorporate AI into education or bring AI to the masses isn’t clear to me. It took a lot of curiosity just to find these sites and I’m guessing Google probably has more out there. What happens when Google ultimately commits to coordinating these efforts into a coherent and effective strategy?

All it took was combining two experimental AI apps to shake the educational world. If the folks behind these experiments flip a switch and start combining these different models and use cases, then we may well have another inflection moment on our hands like we did with ChatGPT’s launch two years ago.

Will AI be Incorporated into Google Scholar?

The elephant in the room no one is talking about is what happens when these AI experimental features jump out of standalone interfaces and suddenly wind their way into massive datasets, like Google Scholar.

Imagine using NotebookLM’s ability to summarize and synthesize up to fifty sources, and create linked evidence within each. Then combine that by using Illuminate’s podcasting feature to do more than just offer an NPR-like summary. Think about the AI generating debates, interviews, deep dive investigations, and even dramatic performances of the connections a user identifies. But they won’t have to stop there. Learn About can then use AI to develop interactive learning environments.

This is how Google pulls ahead in the AI game—leveraging its massive library of existing data using Gemini 1.5’s long context understanding and RAG. We’re going to have to shift our thinking about generative AI beyond the limited affordances offered by chatbot interfaces and start viewing it as a series of techniques to amplify and retrieve information in ways and at a scale that we probably struggle to imagine. That’s going to create some exciting new possibilities in conjunction with a slew of new challenges that will defy simple solutions. For now, these different use cases are scattered, limited, and all too easily dismissed by a public growing wary of the onslaught of AI releases that outpace all of our attention spans.

I found some time to play around with the NotebookLM feature last night and I was pretty astounded by where this is heading—worried and curious and intrigued and all sorts of other things. This is the first time since playing with ChatGPT a couple years ago where I'm this unsettled.

(I uploaded some of my own writings, including an old fiction manuscript from a decade ago, and it was surreal to instantly have "commentary" discussing it, finding connections, identifying key moments, etc.)

I really appreciate these explorations because, TBH, I don't have the interest or drive to do this level of exploring on my own. Some of it is what you say at the end, that I feel a kind of fatigue at the pace and volume of the releases and I'm happy to let someone else figure this out and I'll come and make of it what I will, later.

But also, I think there's some underexplored facets here in terms of whether or not access to "more" is necessarily better. On the one hand, I have literally millions of words of my own writing on education I could imagine loading into a system like this and making sure I'm able to touch base with all of it, but I also experience my own work as a process of filtering over time, so stuff that's 10-12 years old informs whatever I'm doing now, but I don't need to go back to the source material. Maybe I'm rationalizing because I'm lazy, but I don't recognize what that tool could allow me to do as something that's useful for me. Emphasis on "for me," I suppose, but it makes me think that one of the key things we can do for students is to really help them understand their own process and goals around writing. Lately I've been thinking that to help students navigate the changing world, we need to give them as much freedom as possible to see what they make with the tools available and then (through reflection) help them understand what's useful to them and why.

It's also interesting to consider a world where I wouldn't miss out on writing or sources that could be useful to me because I have this tool that helps me survey more stuff (or maybe even all the stuff). Almost daily I come across something that I could have (or even should have) known about to possibly integrate into my book, but now it's too late.

But what if limits around what's available or accessible are actually integral to the process? The goal isn't to write THE book, it's to write MY book. My book is defined by what I read, what I think, what I write. Of course it will be incomplete. That's what makes it interesting. It's part of a broader conversation, not a final verdict on a topic. I wonder what happens if we begin to believe that we have to comb the entire corpus of a subject before we express our own POV's.

Another indispensable post. Thanks.