We’re entering into a period of acceleration with generative AI in education. A university in Michigan is putting two chatbot students in classes where they will interact with human teachers and classmates, including leaving feedback and conducting peer reviews. Not to be outdone, Arizona State University announced a partnership with OpenAI to build tutoring chatbots for first-year writing courses. This follows the Alpha Academy in Austin replacing their teachers with AI.

The accelerationism that has gripped Silicon Valley with crypto, NFTs, and now AI is easy to scoff at in academia. After all, we’ve dealt with the ballyhooed tech breakthroughs from MOOCs and personalized learning, proctoring software and do-it-all learning management systems. Each of these innovations did little for learning but helped institutions sell learning as a product at scale. But lumping Generative AI into this category is a mistake. Many have sounded the alarm, only to find our colleagues dismiss the threat posed by generative AI. I think most educators don’t seriously see AI as anything more than text generation and that may be our undoing.

As the spring semester approaches, a question I’m pondering is what do my students need to know about AI? What about educators, admin, or the general public for that matter? We’ve been throwing around the term AI literacy, but this increasingly means different things to one stakeholder than to others. This makes a unified message on AI challenging, if not impossible.

Smash that Generate Button

Being AI literate will certainly have layers of nuanced meaning for everyone, but I think a baseline we should aim for is understanding. Namely:

what genAI systems do

being capable of recognizing when it is being used

attributing genAI use

considering ethical and pragmatic uses

There are certainly many more. One frightening thing I’ve noticed is regardless of who you talk to about generative AI, many aren’t aware of it outside of good ole ChatGPT. If users struggle to recognize when they are using generative AI within an app they are familiar with, then how can we expect to recognize when the online interaction with, say a classmate named Ann or Fry, is real or automated? Most of the developers have rushed to integrate AI into their existing offerings in ways that are often subtle. Let’s take a look at some rather alarming examples.

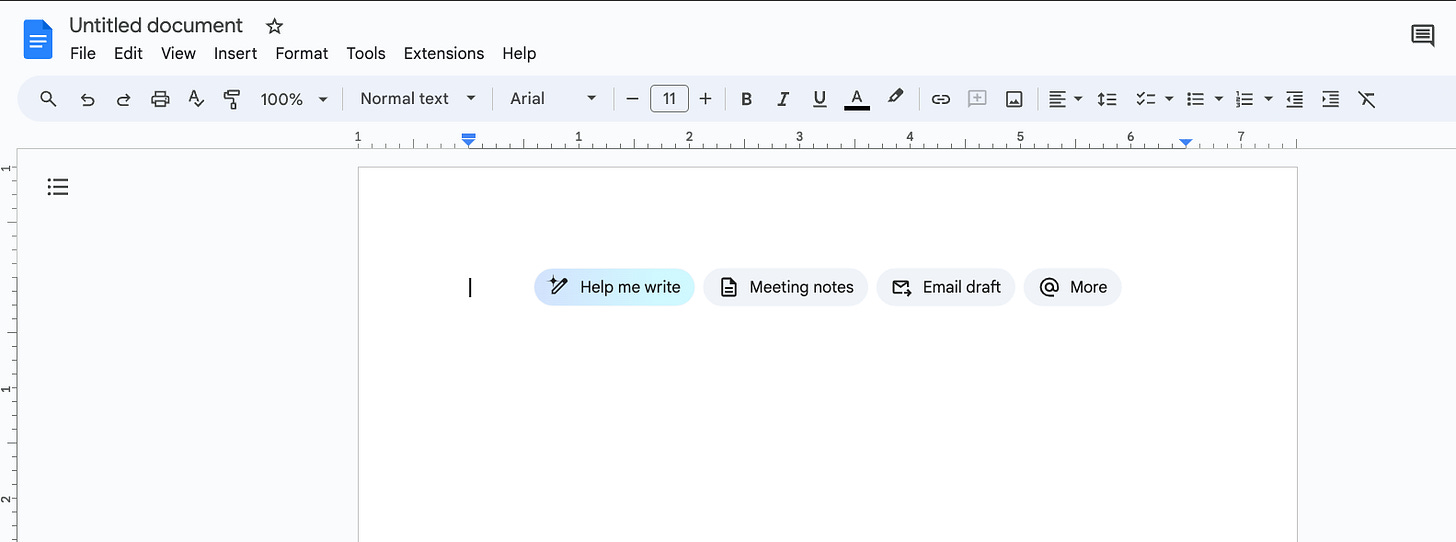

Google Docs ‘Help Me Write’

If you activated Google’s Duet for Workspace, then you now can generate material within Google’s suite of tools, notably Google Docs. All a user needs to do is click on the magic wand with the phrase ‘Help Me Write’ to activate Google’s Gemini Pro model. There’s no warning or indication that a user is activating generative AI. Sure, we can argue that a user had to go to Google Labs and opt-in for this service, but I get dozens of invites from developers each month and can barely keep track of what services I’ve enabled. Does anyone believe the general public, or an 18-year-old, will know what this is without a clear explanation?

Blackboard’s AI Assistant ‘Auto Generate’

Many assume faculty are more aware of generative AI capabilities than students, but in my conversations with fellow educators, I can tell you this is a false assumption. Even worse, there is a presumption among some educators that since they have advanced degrees, they have more than enough knowledge to navigate generative AI tools, without much delving beyond the surface. This may be true for the application of prompting a particular tool for an output, but not necessarily for the implication of what that means to their teaching. Take Blackboard’s AI Assistant. It has been activated for many Ultra users and there are some truly useful instances where it may help faculty; however, the only sign that AI is being engaged is an ‘Auto Generate’ button.

When I’ve tested the Auto Generate feature, the underlying AI scans my course materials to generate an output—I don’t even need to input directions. Sometimes I get a warning about this, like when I click on auto-generate test questions, but not when I create modules, assignments, discussions, or journals. I’m not sure a faculty member understands the full implication of clicking on a button and feeding their lesson plans, assignments, lectures and other various intellectual property into an AI system. And just what AI system is it using exactly?

Further complicating matters, there’s no method within the system to attribute what the AI designed versus what the faculty member created. This forces extra labor on the faculty member to keep track of and identify generative text, or simply not bother attributing what was designed by the AI system at all. Why are we asking students to show and attribute what was generated by AI but not expecting the same from faculty using generative AI systems being deployed in their LMS?

The Perils of AI Detection

Marley Stevens, an undergrad student, failed a class because her use of Grammarly set off Turnitin’s AI detector and is offering her followers on TikTok a front-row seat to the Kafkaesque nightmare of how challenging an AI detection report is a nightmare for students in higher education. In a series of over a dozen videos, Stevens attempts to map out how the professor in question appears to be using Turnitin’s AI Detection report as the sole rationale for failing Stevens. That’s actually against Turnitin’s guidance:

Turnitin's AI writing detection capability is designed to help educators identify text that might be prepared by a generative AI tool. Our AI writing detection model may not always be accurate (it may misidentify both human and AI-generated text) so it should not be used as the sole basis for adverse actions against a student. It takes further scrutiny and human judgment with an organization's application of its academic policies to determine if academic misconduct has occurred.

Stevens's interactions with the professor, dean, and academic integrity office only adds confusion to all the parties involved.

Did Stevens use AI unethically by running her paper through Grammarly? Not by my reckoning, but think how many institutions have shifted the responsibility of identifying ethical AI use or even recognizing if AI is actively being used within an app onto the student? As Stevens says, if AI is baked into everything, how is she or anyone supposed to know if or when a product they’ve used or trusted will set off an unreliable AI detector?

This is a mess, one that dozens of universities have noted and talked about as one of the main reasons they’ve moved to discontinue Turnitin’s AI Detector. The amount of time, energy, and personnel this is taking is enormous and for what outcome? Most academic integrity cases at least attempt to make the process educational for the student—this isn’t a punishment but a chance for you to learn from your mistake. The main sanction in most academic integrity violations for individualized cheating is forcing the student to retake the class. But what on Earth is Stevens or the countless other students who are accused of unethical AI generation supposed to learn in these instances? Is Stevens’ professor going to teach a module on AI literacy, like a writing instructor might teach a module on plagiarism? I doubt it.

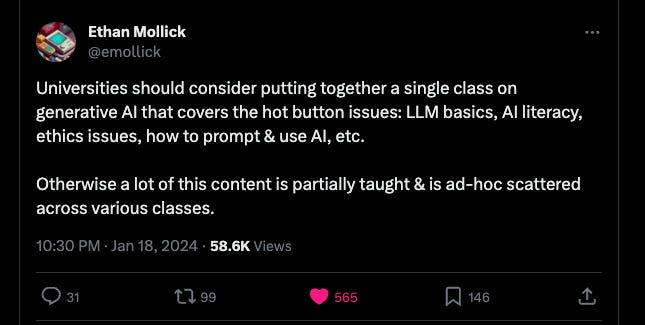

We Need Courses on AI Literacy for the Fall

It is time to bite the bullet and commit to train faculty, staff, and admin in AI, and develop general AI literacy courses for all students. The cost will be high, but ad hoc approaches to AI literacy outside of top-down messaging aligned with institutional goals are only creating pockets of knowledge. It should be clear to all that most institutions will be dipping their digital toes in something related to AI in 2024. Advocating for training should be a priority. Unfortunately, our bureaucratic structures inherent to higher education are hindering any coherent approach and this in turn will keep higher ed in perpetual crisis. Many of you are likely nodding along, as this isn’t news for any of the myriad problems in higher ed—it’s the norm!

What’s different about generative AI is if we don’t act coherently, the chaos risks destabilizing the very foundation of what makes a college education possible and worthwhile. We’re soon going to witness students not only submitting assignments with AI, but also faculty designing assessments, assignments, feedback, and even grading through AI. What then is the point of a college education?

The dangers arising from automating learning are immense and so is the risk this poses for labor in education. I’m not being hyperbolic when I say, that if this acceleration continues, we aren’t going to have an educational system like we do today. We’d previously heard from McKinsey that most knowledge jobs were highly exposed to automation from AI systems. Now, the International Monetary Fund’s recent report on generative AI and workforce amplifies this alarm. The IMF forecasts that 60% of jobs are highly exposed to generative and a whopping 33% of jobs today may well be redundant by the 2030s.

The best way, or perhaps the only way forward, is being able to get as many people to understand the stakes and consider the implications. Generative AI isn’t going anywhere, but we have a great deal of agency and control in how and who uses theses systems and being able to decide what is and is not automated. Will that be true six months or a year from now? If we respond with apathy or dismissal to questions about how generative AI could impact areas like education and employment, we risk ignoring the transformative potential of this technology until it is too late for meaningful public input, as has happened with other disruptive innovations. We must take generative AI seriously now and make decisions about its ethical adoption while we still can.

If any of these issues are to be addressed with the urgency Marc suggests, administrators in particular are going to have to significantly ramp up their learning into how genAI is actually being used by teachers and students and start engaging stakeholders in serious conversations about the ramifications generative AI poses going forward. My limited and mostly anecdotal experience as a 30 year veteran K-12 independent school teacher is that virtually every admin I know (and it is the same talking to teachers from other schools) - Heads of School, Division Directors, Department Heads, and even Academic Deans (and these are likely to be the decision makers on virtually all policy decisions surrounding AI use in schools) are woefully ignorant of even the most basic AI literacy beyond "catching students cheating." The task Marc outlines is daunting for all sorts of reasons but to me the biggest one is the asymmetrical level of knowledge within schools. In most schools, there may be a handful of teachers on the cutting edge of genAI who are flying blind with little to no direction from their supervisors or admin. Adding to the confusion is the haphazard and sporadic ways new genAI tools are being introduced (as Marc says, it's not just ChatGPT - there is voice, music, video, etc...) weekly, making the AI literacy task even more challenging. This is why I am looking for or would like to be part of a Summer Institute dedicated to AI literacy for all K-12 stakeholders, in-person or online. If anyone knows of any program that fits that bill or would like to be part of helping to organize one, please feel free to reach out. I have been following the developments in gen AI disruption, primarily at the K-12 level, but I share all of Marc's concerns.

Great post! Thank you for sharing your thoughts. IMO, we need a 'systemic capstone' for AI Literacy across all lifelong learners (by curricula, major and job role/function). It's something I am passionately solving for currently w/ Solvably's AI Centers of Excellence (check out www.solvably.com, select "who it's for" upper right then "AI"). Imagine if every student (or professional for that matter) not only participated in a project to understand and apply AI to a real-world challenge relative to their curricula (or job) but did so in a fun, engaging way, with evidence(!) and developed soft skills as part of that process? As the urgency dials in, we will get to scale fast enough - it has to. Pls let me know if you, or anyone on this thread would like to collaborate! Stay curious. - Angelo