There’s No Turning Back

Our digital interactions are forever changed

In a matter of months, Microsoft and Google will upgrade their Office and G suite of tools with generative AI, greeting users with the choice to generate content or write organically—each time a user opens a document. This represents a profound challenge and opportunity for education. We have little choice but to arm ourselves with knowledge to prepare for a world where writing will include synthetic text. Google has already released a slew of GenAI features to Beta testers of Google Labs, including rolling out the feature in Google Docs, framing generative AI as “Help me write.”

Google also released the feature for Gmail

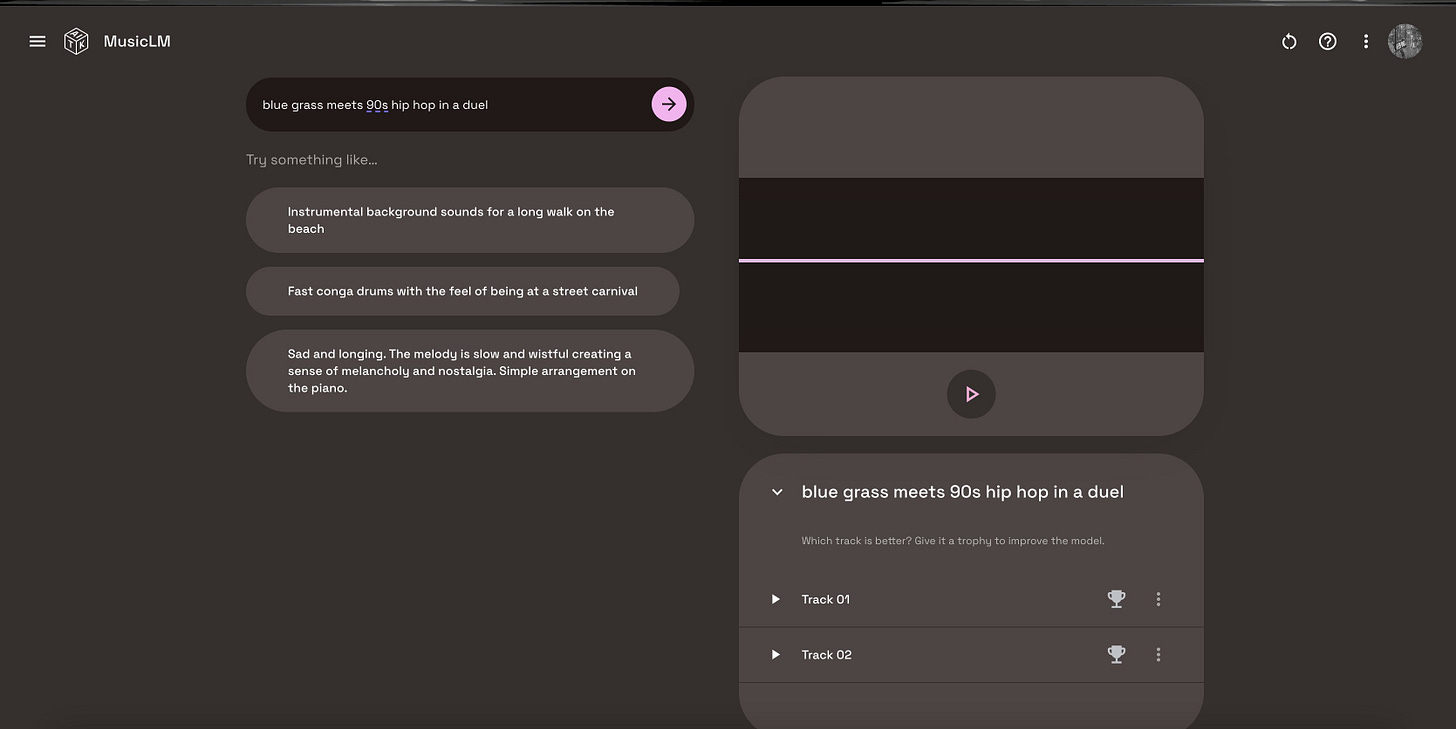

Rolled out a text to music generator dubbed Music LM

And integrated GenAI in Google search with search generative experience

Preparing for the Fall

I’ve helped created an AI Institute for Teachers at the Department of Writing and Rhetoric at the University of Mississippi, with support from the Institute for Data Science, to offer educators training in understanding the technology, exploring the ethical use of generative AI in education, and setting boundaries with students to promote academic integrity.

I just completed the first round of training, a dizzying day and a half of workshops, talks, and panels. It was an amazing and exhausting exercise, one that will need to be repeated many times in the coming year. We are all entering a field that is evolving in real time. Barely a week passes without a new announcement about how Big Tech is committed to scaling generative AI.

Anthropic’s language model, Claude can now read 75,000 words as an input, allowing a user to prompt novel-sized inputs.

Microsoft announced they are moving to include generative AI directly into their Windows 11 operating system.

And OpenAI opened up GPT4 to hundreds of plugins, allowing it to pull information directly from the internet.

There are no best practices for dealing with generative AI in education; we must view it as an emergent practice and collaborate across disciplines, departments, and colleges, to develop methods of exploring generative AI’s impact on student learning. Even Microsoft has forecasted that many future employees will need what they are calling AI aptitude, arguing that “working alongside AI—using natural language—will be as inherent to how we work as the internet and the PC. Skills like critical thinking and analytical judgment, complex problem solving, and creativity and originality are new core competencies—and not just for technical roles or AI experts.” New of these are new core competencies for higher education. Indeed, faculty across disciplines work tirelessly to improve all these areas with their students. Microsoft may identify such skills as crucial for AI aptitude; however, I’d say that the skills we need to teach are AI literacy.

What does it mean to be AI literate? It means being able to exercise critical judgment about when to employ generative AI and when not to use it. To be AI literate is to hold a healthy skepticism, to parse AI hype from tech boosters, and be able to understand actual use cases. A lawyer who is AI literate would know that generative AI tools like ChatGPT often hallucinate, and not ask it to cite court cases. Likewise, voters who are AI literate will be better equipped to detect AI generated deepfakes in the forthcoming election cycle. Indeed, an understanding of the underlying technology and ethical issues arising from how models are trained is a societal imperative, because blind trust in new technology can lead to tragedies.

Banning generative AI isn’t possible when it is baked into most writing technologies and detection will likely never be reliable. We’re left as participants in one of the largest techno experiments in history and while some will ignore it, others will embrace it, exacerbating existing inequities. Our power is one of framing. How educators introduce generative AI to students will form their earliest impressions of the technology and this is why making ourselves literate in AI is so profoundly important. We did not create this fire, but we are here to help students understand it, show them how to use it, and above all teach them when not to use it, because while fire can create light and warmth, it also can burn. If we aren’t cautious, we will find ourselves amidst a conflagration, desperately seeking to extinguish the flames.