What Does Automating Feedback Mean for Learning?

This post is the third in the Beyond ChatGPT series about generative AI’s impact on learning. In the previous posts, I discussed how generative AI has moved beyond text generation and is starting to impact critical skills like reading and note-taking. In this post, I’ll cover how the technology is marketed to students and educators to automate feedback. The goal of this series is to explore AI beyond ChatGPT and consider how this emerging technology is transforming not simply writing, but many of the skills we associate with learning. Educators must shift our discourse away from ChatGPT’s disruption of assessments and begin to grapple with what generative AI means for teaching and learning.

Beyond ChatGPT Series

Note Taking: AI’s Promise to Pay Attention for You

We Should Pause Before Automating Feedback

At its core, feedback is a conversation between the author and the audience. It can be complimentary or contentious, but above all, it is a relationship between people. AI feedback is going to change that. OpenAI’s recent demo of their newly released GPT-4o bot emphasized multimodal feedback through live-streaming audio and video. The ability to get instant results from a machine with a human-sounding voice isn’t something we’ve had to contend with in education in the past. Neither is dealing with a machine that scans your facial queues and updates its response based on what it thinks you are feeling. One thing is certain, the dichotomy of “I wrote something, someone reads it and lets me know what they think” may never be the same now that generative AI can accomplish some aspects of feedback, potentially transforming that relationship forever.

Buried in the dizzying flurry of announcements this past week was Google’s Project Astra, a live-streaming universal vision AI assistant. The project Astra demo should make educators wonder about assessment security, academic honesty, privacy, autonomy, and above all what an instantaneous feedback system will mean for learning.

The disconnect between what tech developers imagine students need for learning and what students are actually able to access in school is a divide AI isn’t easily able to cross. All of these breathless demos showing people using their cell phones to emulate learning use cases don’t seem to understand or care how quickly states are moving to ban cell phones outright in K-12 schools. What tech bros and developers appear oblivious to is how much the public has soured over the increasing negative effects social media and other digital distractions have had on students.

Unless we see dozens of states do a complete about face on cell phone bans, I doubt we are going to see this technology deployed into schools on student devices anytime soon. Colleges and universities are another matter. That leaves AI developers adrift to navigate a myriad of existing regulations that districts and individual educators are required by federal law to follow if they want to deploy AI into K-12 public schools.

Feedback Is A Relationship

Gordon Lish may be the most famous literary editor of the past century. His tenure as editor of Esquire shaped the careers of dozens of writers: Tim O’Brien, Barry Hannah, T.C. Boyle, Richard Ford, and Cynthia Ozick, just to name a few. But he’s most famous for his latter work at Knopf in helping establish Raymond Carver as a literary touchstone. Lish’s edits of Carver’s work fully came to light after Carver’s death and served as a showcase of what a good editor’s feedback can bring to a writer.

In this example, the feedback becomes the relationship between writer and author that goes well beyond line-edits on the page. Here, Lish directs Carver’s writing into a style of sparse minimalism the latter would become world famous for. That takes more than reading a piece and letting someone know what you think. Editorial feedback at this level becomes an art unto itself, but it never exits that relational phase—there is a constant tug and pull between a writer’s intent and an editor’s direction.

AI feedback can give a user some thoughtful, even insightful suggestions about where to take a piece of writing, but its feedback is limited to the generic and aggregate average of what AI predicts a user would want to hear. There is no personality, no intent, no ability to shape or persuade an author into changing their writing. That’s still left to the realm of human beings and the labor involved in even creating the most basic feedback is immense. So it should be no surprise to see educators turning to AI to help, but at what costs?

When You Offload the Hard Parts

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

When a teacher turns to generative AI to offer feedback to students they are doing so to regain time. For some this means using the reclaimed time to deepen existing bonds with students, keeping burnout at bay, or using those moments to help students who need extra attention. Viewed from this lens using generative AI for feedback is undoubtedly a good thing.

But let’s slow down and temper our excitement and pause to ask why AI feedback is needed here in the first place. Why does the teacher need to reclaim time? We should be concerned about an educator turning to generative AI to help with their workload by offloading tasks because doing so does nothing to address the underlying material conditions that caused the teacher to turn to AI in the first place. AI might give a user the perception of regaining time by automating a task like feedback, but it won’t reduce class sizes, increase teacher pay, reduce the number of required state tests, etc. all add to overwhelm a teacher.

In higher education, many of those labor conditions are present for the majority of faculty, who are on contingent contracts in non-tenure track and adjunct roles. Having adjuncts teach the majority of classes at universities and community colleges has been the open secret of higher education for decades. Often, faculty have to teach an absurd number of sections at multiple institutions just to make a living. I know. I did it for three years before becoming a full-time lecturer!

Hundreds of thousands of educators work under these conditions in K-12 and higher education, so who should be surprised to see many of them leap at the siren song of using AI to offer students feedback to lessen their workloads? I don’t judge them, but if the material conditions don’t exist to help those faculty do their existing jobs effectively, then why do we assume the uncritical adoption of generative AI would help rather than hinder them?

AI Feedback: The Good, The Bad, and The Generic

What makes all of this so complicated is there are some really good things AI feedback can offer a user. Generative feedback is timely and focused. Sure, much of it is generic, but simple feedback often is. Likewise, a user can repeatedly call upon feedback 24/7—there is no waiting period for a human being to respond. Students can easily call upon AI feedback to test ideas, arguments, feel out counterarguments, or simply get a perspective other than their own. All of these use cases can be good, extremely helpful, and even empowering, but what happens when AI feedback is used uncritically?

We’re seeing examples of faculty using AI feedback with students and not disclosing that it was done by AI, which is a major ethical lapse in transparency and accountability. Even worse, many of these examples are being done in such haste that the outputs aren’t being carefully checked. The problems we’ve seen from students using a machine to speak for them in assessments is coming full circle now that educators are adopting the same techniques, often with little understanding or consideration for the student and what doing so risks to the teacher-student relationship.

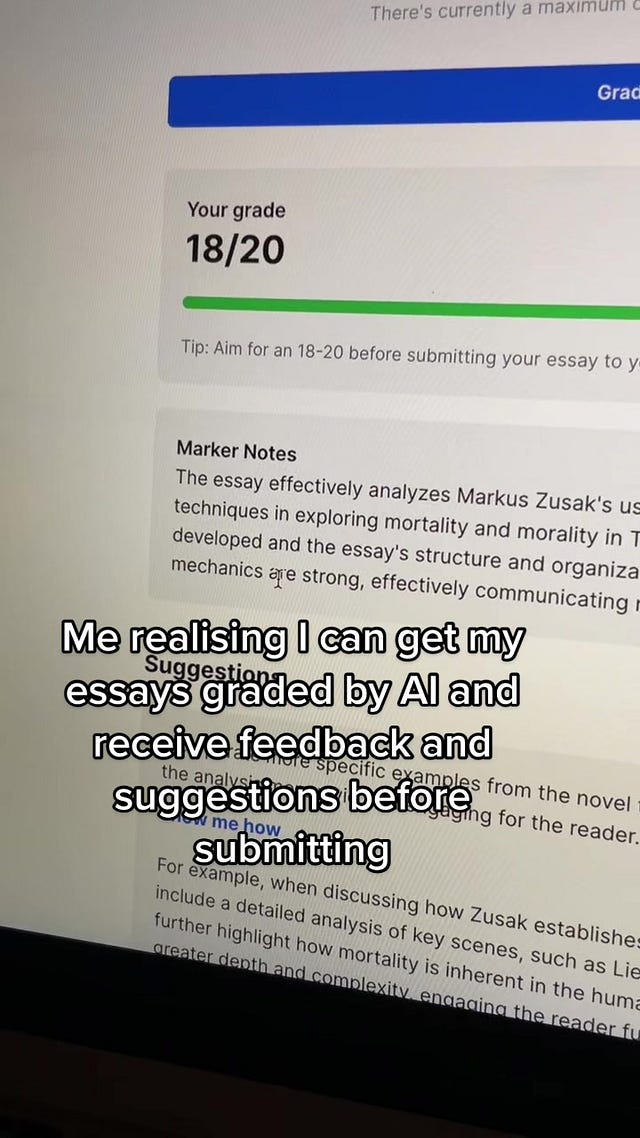

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

When I piloted an AI feedback system with my students this past fall, they overwhelmingly loved having AI respond to their rough drafts in conjunction with peer review. Many of their reflections discussed how great it was to have feedback telling them exactly what they needed to do to fix their writing. That phrase “fix my writing” was a common mantra I kept seeing over and over again within their reflective responses—there was something wrong with their writing and AI could “fix it.”

The problem is writing doesn’t need to be solved or fixed and several students kept asking for the AI for advice over and over again. They didn’t understand that generative AI would always find something to say in response to their prompt—another point to address, a claim to explore further, another three or four counterpoints to rebut. AI is predictive, not a reasoning engine. If it were, it would say a student’s writing is never broken or deficient. All manner of writing is imperfect and that’s fine. When you teach writing to learn, you don’t frame unrealized ideas, poorly worded sentences, or clunky mechanics as problems that are ticked off a to-do list to fix. You sit down with the student and talk with them about their process holistically, talking to them about their ideas, how they’re changing, and how best they convey this to an audience. That’s what learning to write means, at least to me.

If we embrace AI for feedback we have to do so with caution and ensure faculty aren’t doing so as a crutch to bypass the often impossible demands educational systems heap onto them. This matters, because it’s not a leap to see administrators telling overworked faculty to “just use AI” instead of addressing any of the legions of issues keeping educators from excelling at their jobs. And once we normalize offloading human relationships, it’s not too hard to imagine automating the truly meaningful aspects of teaching and learning that form the core of human connection.

One of my favorite moments from today was when I student I taught two years ago walked into my classroom and said, “Hey, I’m wondering if I could get your thoughts on this paper I’m writing.”

I must admit I was hoping you'd show us the kind of feedback AI would have given Raymond Carver.

If a company can train an AI to emulate a professional writing tutor and provide that affordably to public community colleges that would be wonderful. If individual students and faculty uncritically adopt random AI to offload teaching/learning work they didn't value enough to engage in thoughtfully then we've got problems AI cannot fix.