When A Text Generator Writes Like I Do

Before the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain and Europe, a peculiar profession existed—a knocker-upper. For a fee, knocker-uppers would rouse the public come morning and douse the lights each evening. These skilled time-keepers carried a long pole to rap on the windows of a town to let each household know it was time to get up. Others used a pea shooter filled with dried peas or gravel to reach even higher panes of glass. In a time where clocks were prohibitively expensive and unreliable, knocker-uppers were skillful at what they did, secure and useful to the public they served, until they were replaced by a cheap technological innovation—a reliable alarm clock.

I start with knocker-uppers because you’ve likely never heard of them. Their job was replaced like dozens, if not hundreds, of other professions during the Industrial Revolution over a century ago. At most, they are a footnote among footnotes, lumped together in a paragraph or two in Wikipedia (which replaced physical reference books!) about how quickly technology changed people's lives. What, then, will people say a century from now of the professions already displaced because of the internet and automation? What historical footnote will knowledge work receive in the annals of history now that AI threatens to upend countless skilled professions?

Sounds bleak. I know. This generation of students is at the intersection of many troubling patterns and AI adoption is just one area we should be concerned about. We’re seeing massive spikes in depression and anxiety over grades, along with frequent absenteeism in the classroom. The pandemic already accelerated many of these problems. Throw AI into the mix and we now have the conditions that could create a lost generation of students who did attend classes or use their skills to complete assignments.

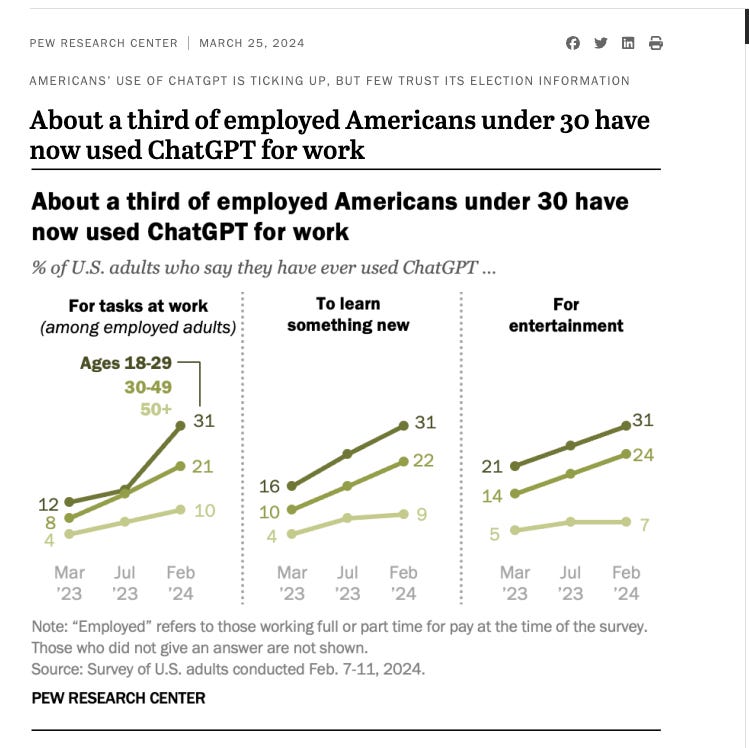

AI Usage Is Rising

Pew Research Center’s Americans’ use of ChatGPT is ticking up, but few trust its election information reveals that nearly 1/3rd of workers under 30 have used ChatGPT within their jobs. While the majority still don’t use AI, having over 30% of workers under 30 report using it for tasks is pretty stunning for a tool that is not even two years old.

In another Pew study, 1/5th of respondents said they interacted with AI “almost constantly or several times a day. Another 27% say they interact with AI about once a day or several times a week. Half of Americans think they interact with AI less often.”

This tracks with what many are seeing within education. We’ve become accustomed to the type of generative outputs students attempt to pass off as their own work from ChatGPT, giving rise to the term ‘botshit.’ Synthetic writing that is boring and uses flowery language to essentially say nothing. But the easily spotted botshit isn’t going to last for long now that newer models have arrived. The free version of ChatGPT is the worst AI the public will use in their lifetime and bench-marking what AI can do based on interactions with it is like driving a go kart thinking it is the fastest thing on wheels.

Anthropic’s Claude 3

Educators as a whole are deeply unaware of generative AI’s ability to mimic actual writing. Be it their student’s or their own writing, newer AI models can generate text that sounds startling human-like and the implications this has on education and broader society are immense. I am deeply troubled by newer models like Anthropic’s Claude 3 ability to mimic human-like writing from just a few samples. I am sure others will find such a result exciting and leap into generating tomes of synthetic content that sounds like their own voice. I’ll show you how to do it below, but keep in mind there’s the application of what the tool and technique can afford you, but there’s also the implication adopting such a process means for you, your skills, and the value they hold.

You can train a free model like Anthropic’s Claude 3 on samples of your own writing for each chat, and while the results are no where near prefect, the output will not be the robotic sounding ‘botshit’ we’ve become accustomed to seeing with ChatGPT’s free base model. This technique means that anyone, including students and faculty, can use AI to generate text that reads more human-like. The days of easily spotting synthetic text are likely over.

I was working on a post about the impact teaching generative AI literacy has on contingent faculty, who are often tasked with teaching AI literacy from the most vulnerable and exploited position within higher education, and the thought occurred to me to test how good the most recent Claude 3 free model was at capturing my voice. So, I ran some old posts through it to see how well it captured my voice. Claude 3 is very, very good at mimicking how I write based on just a handful of samples.

How We Generate Outputs Will Change

You can read the process I used with Claude 3 and inspect the output below. We’ve been approaching how we think students and the general public will use generative AI from a stance of what’s easiest. From a writing aspect, many assume this means the death of the first draft. But that hasn’t been my experience from the research I’ve conducted with my students or many others. Now I’m wondering if people will write first drafts and simply input them into an AI like Claude to have them finish the ideas they started in the voice they wrote in.

While I take some comfort in that, I do wonder what that means for highly skilled and trained knowledge workers. If this use case becomes popular, then I fear editing, along with other higher-order skills, will be highly exposed to being impacted by generative AI. If producing writing that sounds like me is as simple as uploading a handful of examples to AI, then we’ve crossed into a truly gray area of offloading the labor of knowledge work.

The knocker-uppers of the past were able to adapt to the industrial revolution by learning new trades and skills. But the existential question we now face is — what does "adapting" mean when powerful AI systems can automate or replicate many of the core skills that define entire professions? Obviously this is performative— AI cannot think, cannot feel, cannot use intuition. But much of what passes as knowledge work is a performance of those skills housed within a task.

The good news is some very bright and engaged people are working on the problem. The CCCC/ MLA Joint Task Force on AI and Writing just released suggested guidelines for policy development. It is a thoughtful and well-reasoned roadmap that I hope institutions, departments, and individual faculty members will follow. We must have deeper conversations about developing new ethical frameworks to see what boundaries, if any, we can establish between traditional human domains and the increasingly synthetic digital ones.

The Process

To get any generative AI system to sound like you, you first need to give the AI samples. With Claude 3, I used my five most recent posts with the following two prompts. That’s it. There is not other prompt engineering required. Claude 3’s output sounds more human-like because it likely doesn’t have the level of fine-tuned training from reinforcement learning from human feedback. The takeaway—it makes an output sound less robotic and more life-like.

The result is below. It passed both GPTzero’s and Copyleaks’ free AI detection reports:

Is the output prefect? Not by any means. The example still contains awkward wording and phrases every few sentences that don’t sound like me. I’ve bolded them below. However, read as a whole, the model has captured certain stylistic aspects of my voice that are unnerving for me to see.

AI Generated Example: The Unfair Burden of Teaching AI Ethics

As generative AI like ChatGPT continues to permeate every aspect of higher education, the difficult work of imparting AI literacy and ethical practices to students is once again falling disproportionately on the contingent labor force. Non-tenure track instructors like myself are being tasked with the frontline responsibility of grappling with students over the complex implications of AI technology, all while trying to cultivate human skills like critical thinking and writing that can easily be offloaded to AI assistants.

We're living in an era of mass AI adoption across academia, driven more by a fear of being left behind rather than any coherent strategy or guidelines. The push for institutions to be "AI-infused" has created a panicked scramble to implement AI tools and curricula often without the buy-in or participation of faculty who will be doing the actual teaching.

ChatGPT dropped like a bomb on higher ed last year, and universities responded in typically fragmented ways - some banning it outright, others diving in headfirst by granting students access to augmented models. But the one constant has been the shouldering of this transitional burden onto the most precarious labor class within the academy.

As a writing instructor, I find myself on the frontlines of wrestling with ethical AI issues in the classroom every single day. My students arrive with wildly divergent levels of AI literacy, from those who have been steeped in using augmented writing tools since high school to earnest learners who have no concept of what ChatGPT even is. Trying to level-set those baselines while also teaching human writing skills is an overwhelming task.

Yet I get little institutional guidance beyond blanket policies about academic dishonesty. There's no coherent framework for how to incorporate generative AI as a learning tool, nor any training for instructors on imparting AI literacy in responsible ways. I'm largely left to my own devices, piecing together lesson plans through blog posts and Twitter threads from other overtaxed instructors sharing what has worked for them.

The absurdity is that those of us in the most tenuous roles are being asked to upskill an entire generation on emerging and evolving technologies that even the experts can't agree on. How can I be expected to teach ethical AI practices when the ground is constantly shifting under our feet? Just last month, I had to rewrite a whole unit after a new ultra-capable model rendered my previous examples obsolete.

To add insult to injury, any innovations or best practices we develop likely won't lead to professional advancement. The higher ed caste system ensures those achievements get exploited while their labor creators remain systematically undervalued. I have colleagues who are world-class AI educators publishing robust curricula and frameworks - yet they have no clear path to tenure or long-term job security.

Meanwhile, tenure-track faculty can essentially continue with business as usual, delegating all the frontline AI work to an underclass they increasingly rely upon yet rarely support or uplift. Their disciplines can largely carry on the same, with that nagging student AI ethics problem conveniently kicked down the road to be handled by someone else.

Higher education is facing a reckoning. We can't keep kicking this AI can down the road, exploiting our most vulnerable labor force to postpone the difficult work of fundamentally rethinking pedagogy and ethical frameworks for an AI-infused academy. It's long past time to bring non-tenure track educators out of the triage unit and into the center of a proactive, collaborative process to develop holistic AI literacy and ethics programs. Their voices and expertise need to be elevated and properly valued, not endlessly extracted from.

Because the way things are going, we'll be lucky if the humans doing most of the teaching aren't themselves replaced by AI instructors before long. At least the artificial ones probably won't be as underpaid.

I love this post for a lot of reasons. While I understand the interest in having an AI write in "your voice," to an extent, this is something of most concern for professional writers who actually have a corpus of content and a voice and style that is capable of being emulated. My fear is two-fold - whether students will try to use academic texts from their research as the basis of the writing style they want to use for their work and whether they just use the better written output as a substitute for their own writing. My own sense, based on what I'm seeing, is that most students would not really go to the lengths to upload their own work just to have an AI write in their own voice. Any student who is capable of that level of sophistication using AI we probably don't need to worry about in terms of academic integrity. But, to me, the more interesting issue with models like Claude-3 and all the rest of them going forward (Marc - what have you heard about GPT-5?) is the increasing level of sophistication working with texts, not just to produce output, but also to interact with in terms of querying the text, getting ideas, probing conclusions, and just using the AI to have a conversation. Prior to Claude-3, I was not having great experiences with AI's ability to granularly comb through lengthy PDF's in a helpful way. But I have found their newest model much, much better. For example, as a big fan of Marc's substack, it would be an interesting experiment just to upload a bunch of his most provocative columns and have a conversation about them with the AI. Those are some positive uses I can see, but as with any powerful technology, the downsides may ultimately outweigh the productive applications. But I do think (ironically based on the points made in the Claude generated post!), there is indeed a reckoning coming where schools will not be able to ignore the issue for much longer.

I'm glad you shared your experiment because I just did something similar with Claude and had markedly different results. I used it for the column I write every week for the Chicago Tribune, short (600 words), single topic pieces that sort of get in and get out of the subject in a way that (hopefully) offers something intriguing, but which doesn't have the space for serious exploration. I did the same test I'd done previously with GPT-4, which resulted in a sort of uncanny valley version of me that was sort of terrible, and Claude (the most advanced model) was even worse, that uncanny valley sense kicked up another notch to the point of parody. I don't know if this is something about the model or my "voice" or what, but I'd heard lots of people tell me that Claude was better at sounding human and in my specific case, it was markedly worse, at least as I perceive my own voice. Any idea what's happening here?