Our Obsession with Cheating is Ruining Our Relationship with Students

AI detection isn’t going to work—but that’s not going to change our desire to have a tool to detect what work was written by a human vs. generated by an AI transformer.

As the technology to generate writing with AI ramps up, so does the production of AI-detection tools that attempt to curtail “cheating” by using them. But the bevy of AI detection tools on the market aren’t keeping up with the speed of AI’s development. Because they are using older versions of GPT as the main component of their detection mechanism, they often misidentify human-composed text as AI-generated or confuse AI-generated text as human-generated. And while OpenAI is working on a watermarking scheme that uses cryptography to mark text generated by a transformer, even their lead engineer admits this would be easy to defeat by simply copying a generated output into a different language model.

Why are we so obsessed with catching students cheating?

We don’t believe students want to learn. This profoundly misguided notion has broken the trust we’ve tried to establish with our students. Jonathan Malesic’s recent op-ed in the New York Times reminds us all that our students want to learn, to be seen, to be heard. Like our students, we all thrive when we are open to learning new things and having our assumptions about the world challenged. Malesic’s call for humility in this age of “knowingness” is a profound departure from a culture that views not knowing something as akin to failure:

Universities are factories of human knowledge. They’re also monuments to individual ignorance. We know an incredible amount, but I know only a tiny bit. College puts students in classrooms with researchers who are acutely aware of all they don’t know. Professors have a reputation for arrogance, but a humble awareness of the limits of knowledge is their first step toward discovering a little more.

To overcome careerism and knowingness and instill in students a desire to learn, schools and parents need to convince students (and perhaps themselves) that college has more to offer than job training. You’re a worker for only part of your life; you’re a human being, a creature with a powerful brain, throughout it.

One of the benefits of a college education is it teaches us how little we know about the world, about how vast and complex the range of knowledges are. Your students want to be there to be a part of that world, to occupy that space with their minds and ideas. College also invites you into a discussion about that knowledge, which tests your limits, allowing personal growth. When we take a stance on students and preemptively assume them to be cheaters, we are essentially denying them entry into this space.

Josh Elyer is correct. The current freak-out panic over ChatGPT mirrors the panic that drove institutions and faculty to plagiarism detection software in the first place. Decades later, plagiarism detection software has conditioned us to easily access a tool that we hope will prove to us a student’s writing is their own. We don’t think about the fact that this tool helped accelerate contract cheating and creates a culture of mistrust. We don’t think about how the use of these tools has set up a situation in which companies are harvesting unfathomable amounts of data from our students. We mistrust our students’ desire to learn in such a profound way that many don’t give a second thought to using AI-detection software that tracks students’ eye movements and may misflag female students of color at far higher rates than white males.

AI Detection Examples

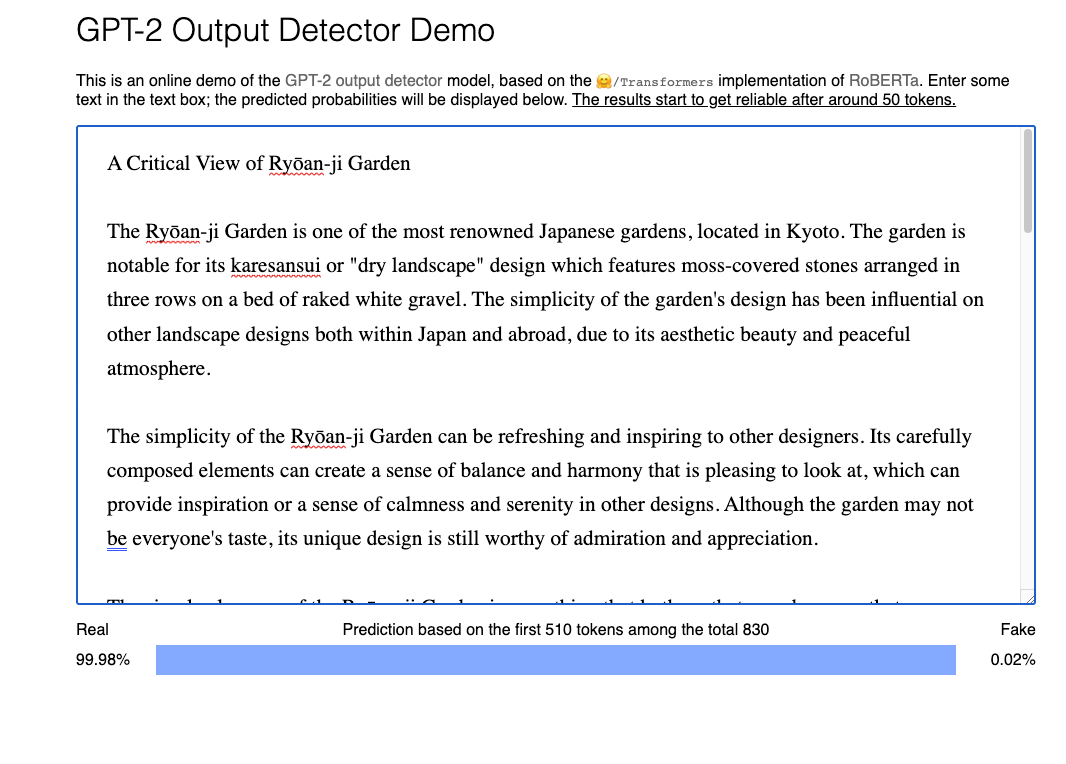

You can play around with a number of the AI detectors below. Sometimes they work. Sometimes they don’t. Is that really the bar we want to use in so-called AI detection? I’ve included screenshots of the detectors mislabeling an AI-generated essay I created with a GPT-3 powered app in October. In each case, it labels the generated essay as human writing.

Huggingface’s roBERTa powered Output Detector uses GPT-2 to try and detect AI

IBM’s Giant Language Model Testing Room (GLTR) also uses GPT-2 to try and detect AI

And then there are the waves of clones and eager developers rushing to sell terrified educators something to detect AI.

Crossplag decided to use roBERTa alongside their plagiarism detection and at least includes the caveat that the system doesn’t work well enough to be deployed to institutions at this time.

The newest one, GPTzero, also fails to detect the AI-generated text and likewise appears to use some form of GPT-2.

Trusting our Students

When we use AI to catch AI, we’re making a decision to put our trust in systems that we do not fully understand under the vague promise that “at least this is something.” Maybe that’s what people need, but how long will it be until a faculty member takes one of these unreliable reports as gospel truth and brings an innocent student up on charges of academic misconduct that are false? Think of the damage this will further cause to the already frayed relationship between teachers and students.

I, too, have used plagiarism detection software in the past. Hundreds of my students have submitted thousands of essays through such services, knowing their words will be assessed against a large database to discern similarities to other essays. I have required the use of this service under a misguided belief that a rote and imperfect method of detecting cheating is more important than creating a culture of trust.

We’re going to have to stop panicking and educate ourselves about the technology and think about what boundaries we’d like to put into place with our use of the tech and our students. While the current moral panic is about students using GPT to cheat, I imagine this is going to shift rapidly when folks realize that faculty can also use the technology to leave formative feedback on student essays. To echo Mike Sharples, “Students [will] employ AI to write assignments. Teachers use AI to assess and review them (Lu & Cutumisu, 2021; Lagakis & Demetriadis, 2021). Nobody learns, nobody gains.”

We’re going to have to search for moments of learning. One way of starting this exploration is to heed John Warner’s call to stop automating the writing process. Students write predictable, formulaic essays and teachers leave similarly predictable, formulaic responses. What was learned and what was gained in such a system? The reasons why we’ve adopted this structure are based on convenience and labor. It’s easier to teach the form of an essay than it is to teach a person the skills needed to develop as a writer. To do that, you need small classes, a reasonable teaching load, and well-compensated faculty.

Here are so-called GPT detectors that don’t reliably work:

For your listening pleasure:

Great articles mentioned in this piece:

John Warner ChatGPT Can't Kill Anything Worth Preserving

Traci Arnett Zimmerman Twenty Years of Turnitin: In an Age of Big Data, Even Bigger Questions Remain

Jonathan Malesic’s The Key to Success in College Is So Simple, It’s Almost Never Mentioned

Mike Sharples Automated Essay Writing: An AIED Opinion

Deborah R. Yoder-Himes, et all Racial, skin tone, and sex disparities in automated proctoring software

All hail your last sentence! :)

If we develop assignments that are not susceptible to artificial responses our students' learning, and ours, would be so much richer. And the work in developing such learning with our students would stretch us, too, to think in terms of our society as a whole, not in terms of a grade book and a sigh of relief at the end of term...