Reading in the Age of Social Media (and AI)

I’ve published quite a bit about AI’s impact on reading and I’m still not entirely sure how students or the general public will use AI reading assistance. Many educators are drawn to NotebookLM’s ability to summarize and synthesize content you upload to it, while others find other tools, like OpenAI’s new text leveling feature in their canvas feature, to be antithetical to the notion of assigning critical close reading. Regardless of how we feel, or our stance, I don’t think we can argue that generative tools have the potential to impact our reading habits. The greater point, though, is why are we moving so rapidly to ship technology that transforms, offloads, or changes those habits?

Ethan Mollick’s recent criticism of AI developers should be asked by all. Namely, what is all of this technological innovation hurtling us as a society toward? If copilots and agents of today suddenly become AGI, what will that look like for my daily life? Asking what the purpose of things is pretty standard for most new inventions and applications. We should all be concerned when the response is collective silence.

Reading With and Without NotebookLM

Justin Cerezina’s Like A Book Elegantly Bound, In a Language We Can't Read Just Yet does a excellent job of breaking down many of our current reading habits with and without technology. His key takeaway—reading online is complicated. We can access far more words online than in traditional print, faster, more efficiently than at any other point in history. But reading with one method isn’t necessarily better than another. We might want to regularly rotate print, digital, and even explore new methods like AI reading assistants. In sum, we should all start exploring a little bit. Here’s Justin summarizing his experience reading an online study via screen, printout, and using NotebookLM.

This is to say I read (or consumed it) in multiple ways. I often tell my own kids, “There is a world that exists as it is. And there’s a world that exists as you’d like it to be. Only one of these things is true, no matter how much you might dislike that.” There are tools out there which improved my experience of reading the article. These tools are new in many instances. These tools have also merely amplified my reading experience.

Essays/ Articles/ Interview about AI Reading Assistance

Below are seven pieces from 2024 about AI reading assistance I either authored or was interviewed for. You’ll notice a few themes—I’m worried, frustrated, I don’t think we are really talking about the implications of AI and reading.

Essay. December 2024 The Chronicle: When AI Does the Reading for Students

Interview. November 2024 EdSurge: New AI Tools Are Promoted as Study Aids for Students. Are They Doing More Harm Than Good?

Interview. August 2024 Tea for Teaching Podcast: Beyond ChatGPT

Interview. June 2024 Intentional Teaching Podcast: AI’s Impact on Learning

Interview. June 2024 The Chronicle: Professors Ask: Are We Just Grading Robots?

Essay. May 2024 Substack: No One is Talking About AI's Impact on Reading

Article. April 2024 Teaching and Generative AI:Pedagogical Possibilities and Productive Tensions Automated Aide or Offloading Close Reading: Student Perspectives on AI Reading Assistants

How We Read Today

We live in a visual age, not a textual one. We’ve long ago traded daily papers for screens—magazines for smartphone social feeds. That some of us (myself included) still get print versions of the New Yorker, the Atlantic, or Southern Living, says more about our status as outliers amidst a frantically digital era. To pause and pick up a glossy page and see static ads that don’t dart across at you is a welcome respite from the always-on nature of our world.

This past year, I started and failed to finish dozens of books—novels, historical fiction, hard sci-fi, and even many Audible books remaining partially finished. I’ve slowly been working my way through Patrick Radden Keefe’s gripping and brilliant Say Nothing for the several months and then I saw a trailer for the limited FX series based on the book. Granted, the book is six years old, but in my mind, I felt like I had more time before my eyes had to confront the made-for-television version of the narrative I was reading.

I first noticed this change in my own reading habits late last year when I started going on TikTok and Instagram to investigate how influencers were selling students various generative AI products. Tiktok’s algorithm started feeding me more videos based on my interests and suddenly I found myself spending thirty minutes or more bouncing between junk food for my eyes. SNL’s Tiktok skits capture the absurdity of our moment shockingly well.

Brain Rot, Social Media, and AI

In our very online world, brain rot was aptly chosen as the phrase of the year. Days later, the U.S. Federal Court upheld the TikTok ruling, forcing the sale or ban of the app in the United States. The latter is an entirely political decision, but one I welcome given the apps’ impact on my attention span. It’s hard for me to admit, but TikTok and social media in general have fried my ability to read this past year.

Brain rot is defined as “the supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as the result of overconsumption of material (now particularly online content) considered to be trivial or unchallenging. Also: something characterized as likely to lead to such deterioration.”

Social media has transformed our daily habits in so many ways that it’s hard to accurately describe its overall impact on our culture. For me, that it has mostly meant I haven’t had the traditional focus to read deeply with a book. I spend a great deal of time keeping up with AI. Doing so has only been possible if one was plugged into X, Linkedin, Bluesky, Discord, Instagram, and yes, TikTok.

Now that we have AI reading assistants, the temptation to use them to summarize articles I don’t have time to read is alluring, but I don’t think I’m interested in the illusion or simulation or reading offered by a generative summary alone. Though, there’s some nuance here. While I’d like to return to the joy of physical books and the privilege of reading, I don’t think I’m necessarily opposed to putting an AI reading assistant into my rotation as a way to help me navigate information from studies or other material.

How Has Recent Technology Impacted Reading?

Before NotebookLM and its instant podcast feature dazzled educators, there existed a service that could summarize and create podcasts of nonfiction books called Blinkist. For years the app was little more than a novelty— promising users the experience of reading a book in as little as 15 minutes. A technological solution to match our dwindling attention spans for our very busy lives. But as critics noted nearly four years ago, the service offered the appearance of reading a book rather than the reality of reading.

Blinkist is a novelty, one I can hardly argue is a success. But I feel like Blinkist and new AI tools focused on reading speak to our cultural moment in ways we may be too busy to slow down and consider.

Our ability to pay attention has been altered by how often we haunt digital spaces. The stories we tell are often sound bits instead of full-on narratives. The videos we watch are reduced to concise clips—snapshots of scenes. Even the traditional news we read has been Axiosed into short chunks— summaries of summaries.

Is this bad or good isn’t really the point? The objective fact is that our habits are changing and are doing so at an increasing pace. I cannot think of any habit more profoundly associated with education than that of reading, and now that generative AI is here we cannot ignore its impact on reading habits by dismissing it as novelty.

Books as Objects

Books are made to be read. Normally, that wouldn’t be a provocative statement. Before AI we were awash with a much different sort of discourse—books as beautiful artifacts arranged via color—just like a rainbow.

Shockingly, giving one’s bookshelves the Marie Condo color treatment pissed people off. We’ve traditionally arranged books via author or theme or idea but by color? The heresy of arranging books by shade reduced the book to solely a visual object, one that simply sits atop a shelf based on its visual appeal.

When the pandemic hit, people found themselves stuck behind Zoom windows and this gave rise to the “Washington bookshelf”—services that would provide you with books that had the right authors to adorn your background.

The performative nature of “do I have the right books behind me” during a Zoom is an apt backdrop for a culture that values the idea of being well-read, but doesn’t feel like we have the time or attention to make that a reality.

The newish trend of books arranged backwards to hide their spines is far worse. Why even worry about finding a book to read? After all, the goal is to fill space with things.

I highly doubt we’d have any of this discourse around books as objects if it weren’t for social media and Zoom. Like many internet driven trends, is doesn’t have a long shelf life (yes, I went there!) However, it show us how our very online culture quickly transforms our tastes because of the algorithms we use each day.

AI and Publishing

Most authors don’t want to adopt AI. Authors want their voices heard and will continue to write without AI assistance, but the editing, formatting, distribution, marketing, and even reviewing of future books will likely all be heavily influenced by various forms of machine learning and generative AI. Will reading for pleasure be influenced?

Recently, Microsoft announced it was starting its own book publishing imprint, 8080 Books. They hope to use some of the same technology behind generative AI to “accelerate the publishing process, shortening the lag between the final manuscript and the book’s arrival in the marketplace.”

Microsoft isn’t the only player in GenAI publishing. A newly launched company called Spines promises to use AI to publish 8,000 books per year. Spines isn’t a charity—they “will charge authors between $1,200 and $5,000 to have their books edited, proofread, formatted, designed and distributed with the help of AI.”

Many on social media have scoffed at these announcements, saying people behind them don’t understand books or book publishing. But in an age of Book Tok, AI summarization tools, and businesses selling books as visual objects to adorn shelves for the perfect Zoom background, I think they’ve missed the point. Technology is feeding us what we want at an ever-increasing pace. I can’t go on Amazon anymore and read reviews of books without running across an endless sea of AI-generated summaries extolling how wonderful an author is. The same goes with Goodreads. Most of the self-help section is now filled with AI-generated content in published ebooks. Don’t get me started on the cookbooks. The old model of waiting 18 months or a few years to see a book go to press isn’t going to survive in this AI era.

It’s such an odd twist of circumstance to find physical books suddenly filled with synthetic text. The traditional idea of people buying books to be read doesn’t fit this new dynamic, as few people are going to rush to buy an AI-generated book for the reading experience. What worries me is that 8,000 AI books a year only works as a business model if you bypass the whole reading part and start producing books as just another form of content creation we’ve seen explode across the web in the past decade.

Beyond NotebookLM: Google’s Deep Research and Reading

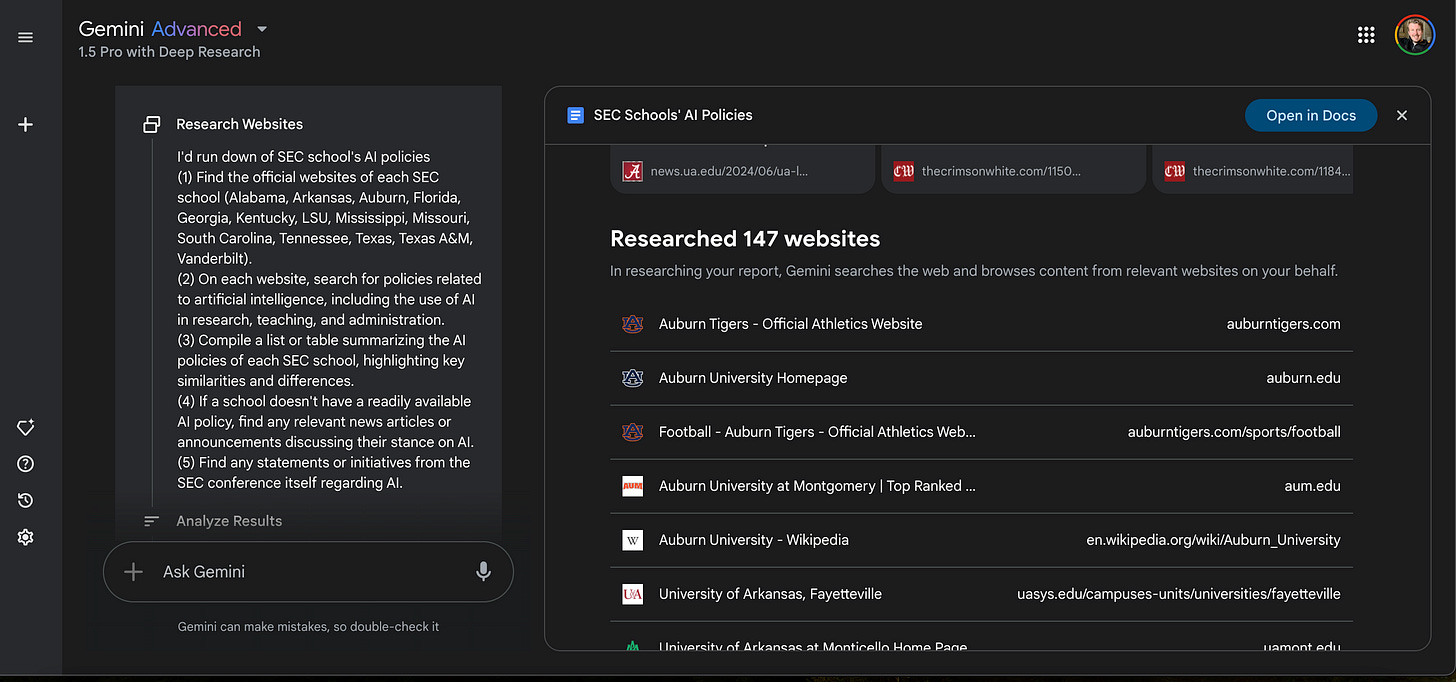

If you subscribe to Google’s $20-a-month Gemini plan, you can access Google’s new Deep Research AI Agent. Running a simple prompt tasks Gemini to create a multistep plan, and then execute that plan using various tools. Deep Research leans on Google search. Each output produces somewhere between a dozen and a few hundred sources. Gemini scans the sources, summarizes them, and then synthesizes each with your prompt. The total time this takes is somewhere between 5 and 15 minutes.

I have no idea how much energy a single prompt consumes, but I’m guessing it is massive. I ran the above prompt about SEC universities and their AI policies for our recent Winter AI Institute for Teachers at the University of Mississippi and Gemini scanned 147 sources! The more practical response I have is how the hell am I or anyone supposed to read 147 sources? I don’t think we are and that’s something we should think about.

Generative AI and predictive AI can do so much more than write an essay, summarize a single text, or be a sounding board. AI research agents like Google’s Deep Research represent something so profoundly alien and new that it's hard to categorize it as a tool, a process, or a technique. In the end, agents represent a bit of all the above. The problem is when you task AI to research for you, you’re ceding some sense-making and agency to a machine. Now, that’s not new or radical. We do so every day for GPS, autopilot, internet search, and so many non-generative things. But when the GPS is wrong we know it and adjust our course, we keep human pilots at the stick because we know autopilot can fail, and we know search isn’t a stand-in for research, but I’m not sure there’s a path to navigate an AI agent that researches and reads for us at scales we cannot match with our human attention. But it is time for us to dig in and explore.

How Do We Teach Reading as a Skill in Our AI Era?

Our reading habits are changing, and so too is our relationship with text. Change is always inevitable, but for those of us in education, AI agents that can read massive amounts of sources is . . . a lot to take in! Our students struggle with book-length texts for many of the same reasons we struggle with focus and attention today. Now that Generative AI can summarize texts and level the words to a user’s reading level. We’re left wondering what this means for reading as a skill.

Time is the one thing that so many students struggle with. I think we all might want to consider flipped models of teaching and give students the opportunity to read during class, with the understanding they do so in device-free zones. In higher education, we only have our students in class for 2.5 hours each week. If you are teaching a reading-intensive course, you might consider what you value imparting to your students.

I realize saying this sounds a whole lot like “let’s return to Bluebooks” as a response to ChatGPT’s impact on student writing. Reading, though, isn’t about an end product. I’d even say it isn’t about process. When I read, I want to engage a another’s thoughts. A book or well-written essay is like crawling inside someone’s skull and seeing how all the gears churn. I enjoy running into ideas that please my worldview and welcome coming across those that greatly discomfort them.

I don’t think we get that from a generative summary, or a condensed text leveled by a machine, often ripping away nuance and meaning in favor of concise bullet points. I’m sure we’ll see some valid uses for AI reading assistants, but I’m not confident those will come in courses that traditionally ask students to read a hell of a lot.

This is a battle I’m fighting both with myself and with my students. We are all more likely to skim when reading on a screen, and so I wonder about what should be done about screens in grade school. Have you read Stolen Focus: Why You Can't Pay Attention by Johann Hari? It really opened my eyes to the severity of our collective lack of attention.

I should have more deep things to say about this (yet another great piece), but my first impulse was to recommend, if you haven't heard it before, HousePlants' pandemic-Zoom-era song "What's With All the Pine?" Listen and you'll know why I recommended it. :)

Thanks as always for your thoughtful work, Marc.

I'm getting to this article belatedly. The belatedness is telling enough: instead of reading medium- and long-form articles on Substack - not to mention books! - I find myself scrolling through Insta reels - the old[er] person's version of TikTok. I can claim I'm doing research when I'm on TwiX or Bluesky, but I can't make that claim for Instagram. I have a huge stack of AI books but I feel like a squirrel as I try to focus. I have read and written on Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, FFS! . None of us is immune. This sense of overload adds to the appeal of the "summarizer" especially for those who are not in critical tech studies and therefore inclined to just apply a tool to a perceived problem.