The very real frustration teachers have over rampant AI usage in classrooms is growing. I think it is fair to say higher education lacks any sort of vision or collective point of view about generative AI’s place on college campuses. Leaving individual instructors to decide their approach to AI is only causing more chaos and confusion among students. Some faculty advocate for strict AI bans, while others take cautious approaches to integrate AI, and likely the largest group of all remains decidedly silent and unsure what to do.

As the fall semester approaches, we’re bound to hear more talk about AI policies, what new skills students will need, and how to curb AI misuse. We’re also likely to hear renewed calls for faculty to redesign assessments. What strikes me is how little conversation there’s been among AI evangelists about how extraordinarily challenging it has been to keep up with never-ending AI updates and the near-impossible task of designing assessments for this rapidly evolving paradigm.

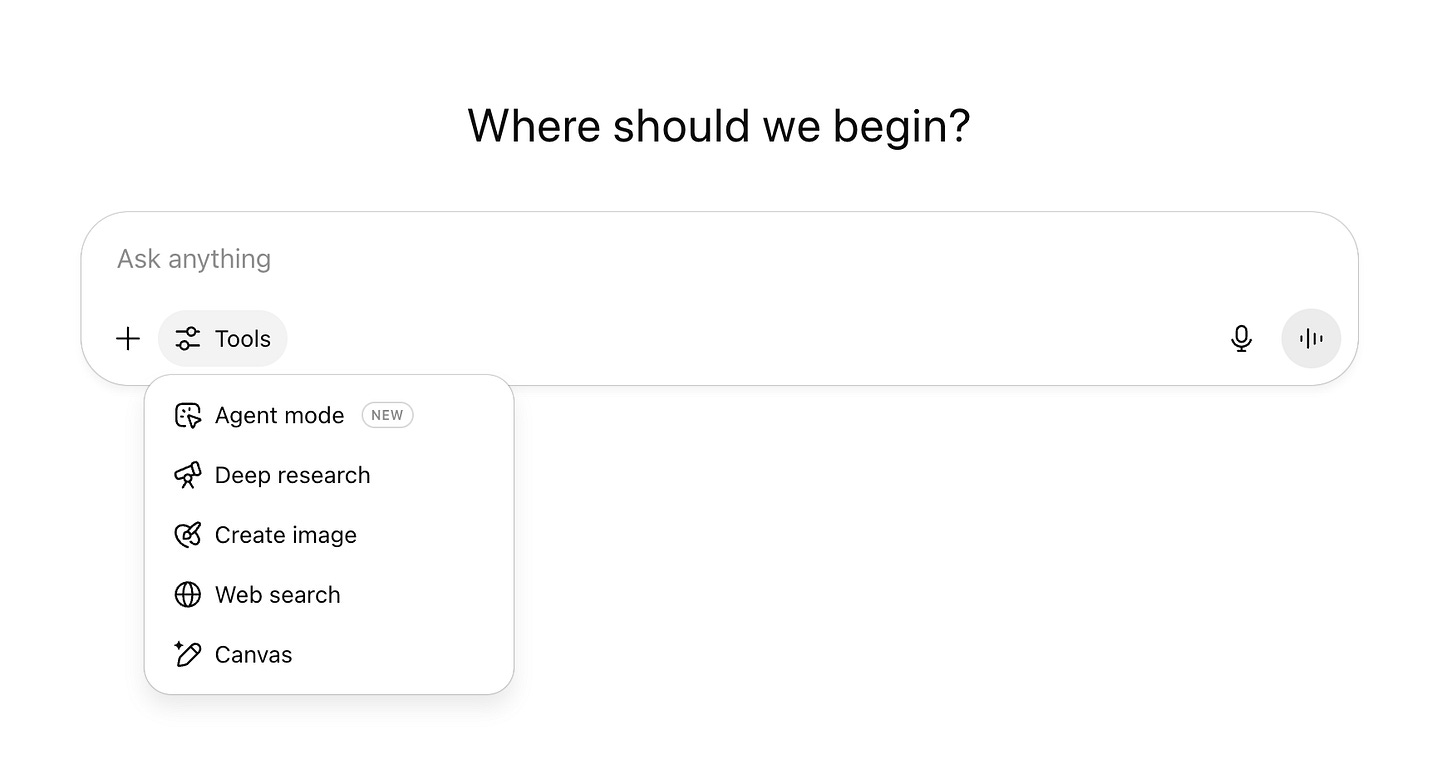

Many, if not most, of the calls to reform assessments appear to equate generative AI with text generation from earlier models powering ChatGPT. That’s a problem. A big one. Those early days of ChatGPT and simple text generation are long gone. They’ve been replaced by multimodal functions. And, yes, even multimodal features have lost their new car smell. So-called reasoning models, deep research, and agentic AI are now all the rage, but for how long before those features are usurped by a new one? There simply isn’t an easy answer for how educators are supposed to redesign assessments to address a technology that continues to evolve around them in real time.

We may be in very serious trouble here because there are no signs that AI developers are slowing down or stopping from releasing their most advanced features to the public for free or at low cost. At this pace, no one is going to be able to harness AI effectively for learning outside of novel pilots that struggle to be repeated. I cannot even keep track of all the models that are in the $20 plus plan, and have no clue what many of them do. ChatGPT’s user interface is a constantly changing mess of features.

ChatGPT’s Chaotic User Interface

Higher education is stuck viewing ChatGPT as it was in November 2022, not as it is today, and certainly not as it may be in the future. ChatGPT is just the interface for generative AI, not the technology itself. You don’t go into your Goodwill store and see an IBM laptop from 25 years ago and think about it as being the same as your current laptop just because it has a similar screen, keyboard, and trackpad as your current device today. The AI models behind ChatGPT are much improved, and so too is the hardware, drastically improving in performance and efficiency of the user’s experience over the past two and a half years.

Which brings us to the society-sized problem that we’re feeling so acutely throughout education—the most advanced versions of generative AI aren’t in some military research lab, but instead are hoisted on the public mere weeks after models are developed in private company labs. That’s absurd to even think about. Even more absurd is the fact that students are some of the biggest users of AI, and faculty are supposed to address that?

AI fluency frameworks in higher education advocate for teaching responsible usage of AI, but none of them talk about the impossibility of our current situation. There is no framework that adequately addresses multimodal AI features that have been available for over a year, and there is very little discussion about how to use reasoning, deep research, or agents in education.

It’s no surprise then to see waves of educators wanting to return to Bluebooks or other in-person exams. After all, how can you be sure what your students know if they cannot demonstrate that knowledge for you in a test, oral exam, or in-class essay? But that’s only part of the issue. AI is now being used by students to learn the material we want to see students show us within those proctored assessments. Learning itself, not simply assessment, is now being impacted by AI.

Last summer, I spent time focusing on AI’s impact on learning outside of text generation with a series of posts about how the technology was being marketed throughout education as a learning aide:

The Beyond ChatGPT Series

Note Taking: AI’s Promise to Pay Attention for You

AI Detection: The Price of Automating Ethics

Instructional Design: AI Instructional Design Must Be More Than a Time Saver

What strikes me in the year since I ran the series is how little conversation we’ve had about AI and learning. In part because we’ve seen shifts in how society is using tools like ChatGPT for companionship and therapy—two fairly alarming use cases that appear to be taking up a great deal of the discourse. The recent report by Common Sense Media about AI usage among teens in the US is a troubling sign about how young people are starting to use generative AI as substitutes for human connection. The survey from Internet Matters in the UK seems to corroborate this.

It’s understandable that the conversation may have moved on to other areas, but with recent announcements like OpenAI’s partnership with Instructure to bring ChatGPT to Canvas, I think it is worthwhile to continue the conversation about how generative tools are impacting our labor and how students learn.

Finding Value and Meaning in Learning

As much as I fear students turning entirely to technology, that isn’t exactly what we’re seeing in the wild. People are using AI in novel ways to do things that may not have been possible before. Take Luke McMillan’s Learning in Motion: How AI Helped Me Build a Motion System (and Learn C++) from Scratch. McMillian used ChatGPT to help him salvage a retro arcade cabinet from the early 1990s. The process of refurbishing the physical structure or the cabinet also meant rebuilding its computer system, along with fixing and writing code from scratch, all skills McMillian didn’t natively have. But what he did have was a good sense of establishing questions he could ask AI to help him walk through the process. His takeaway for students and education:

Students can become architects of the learning process, but only when the challenge is well-matched to their motivation and existing skills. In this project, I was the learner and the designer. I had a clear vision and a strong personal drive to see it through. For classroom use, educators play a critical role in setting up this kind of challenge: choosing a problem that is authentic and meaningful to students, but just beyond their current capability. With the right scaffolding, students can learn to define sub-problems, structure their approach, and engage AI as a partner in implementing their design. But they first need to be given a reason to care about the house they’re building.

That isn’t redesigning assessments because of AI—that’s revising what we assess based on what we value. Young people don’t want to pass through a series of gates simply to gain a degree. Nor do they want to go into debt to find a career that fails to make their work meaningful. McMillan’s final thought is a call to action: “What if we stop trying to assess everything? What if we focused on what truly matters, curiosity, adaptability, ethical reasoning, the capacity to collaborate and create meaningfully? Not everything needs to be graded. Some things need to be grown.”

I think this echoes a great deal of what

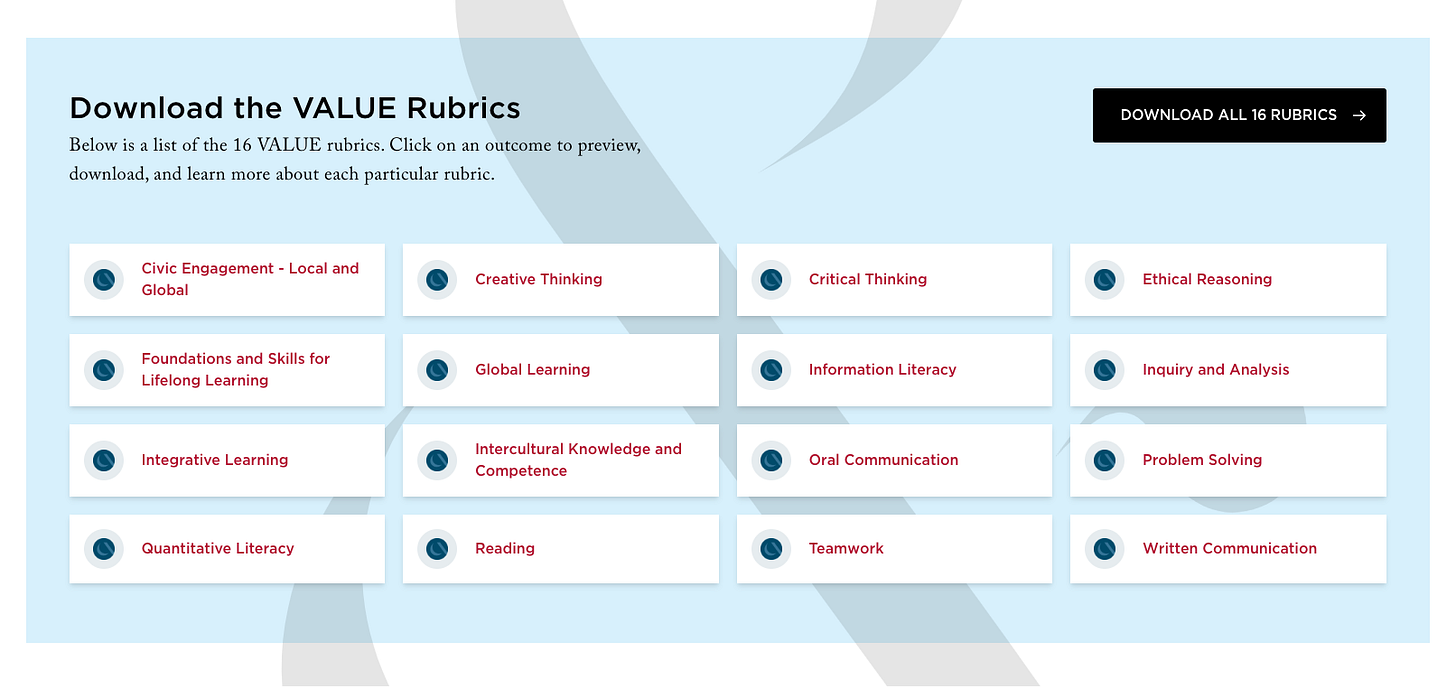

has been calling for in More than Words, and what has been advocating in grading reforms. One area we can start to think about changing what we assess is looking at models, like the AAC&U’s VALUE rubrics, for examples of the types of human skills we want students to practice with and without technology.I don’t care if an AI system completes a math test or achieves some amazing score on some hyped benchmark, like Humanity’s Last Exam. Those technical benchmarks rarely transfer into the realm of human skills. Case in point, we’re likely a generation or more away from robotics that can actually perform even basic human tasks. I’m afraid we’ll all be quite old by the time we see a robot washing dishes for us. But that’s not really the point. Education is about human beings and what they can bring to the world. AI is one of many technologies that can be an interlocutor to learning or an incredible aide to help someone learn. It also serves as a moment for us to see anew existing assessment practices that weren’t exactly meaningful to our students before AI’s arrival.

"AI is now being used by students to learn the material we want to see students show us within those proctored assessments. Learning itself, not simply assessment, is now being impacted by AI."

This is the line that has me ruminating most right now, in thinking about how this impacts skills-driven learning compared to content-driven learning; how to continue to center the process over the product (and make sure the AI "learning" isn't skipping past the process to the detriment of the learner); and how to the skills themselves that are centered in our courses may need to evolve in the years ahead, given the technological capabilities.

Appreciative of this post!

Yes to all of this. It's unfortunate that most teacher's are having conversations about AI as if it's 2023 compounded by the fact that those who opt out are fairly ignorant about what their current capabilities are which are significantly more advanced. But if the conversation moves to safer and more familiar pedagogical ground about the skills and habits that enable the productive use of any tool, let alone AI, that may be the better focus. But the using AI to learn the material itself is very real - I have had multiple conversations with teachers and students in the past few weeks with the key takeaway that poor professors, lousy teachers, and bad communicators are extremely vulnerable. Kids are just going around them and using AI to learn the content. Not sure that's their fault.